|

“Only Crumb Didn’t Forget”: Traces of the High Preserved, and Harnessed

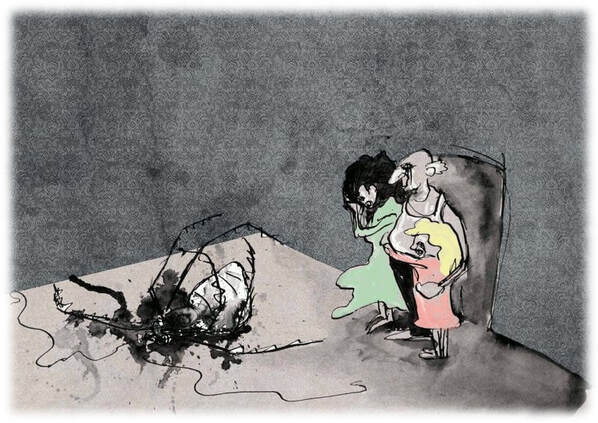

There’s a quote I’ve been turning over in my mind for a while, but alas, I can’t remember it verbatim or even remember who said it. Maybe, then, it wasn’t that memorable? Anyway, it was in the intro to a volume of comics by the artist R. Crumb, in “The Complete Crumb” series. For those not familiar with Robert Crumb, he’s the incredibly sartorial weirdo who basically rewired American popular consciousness with his comix. He was uncomfortable, though, with his place in American pop culture, and so fled to the South of France, where he lives as an eminence grise in exile. That he remains prolific while abroad—and seems spry in recent interviews despite being an octogenarian—is proof that he made the right choice. Anyway, this intro (by Spain Rodriguez or S. Clay Wilson?) talked about the impact of first seeing Crumb’s work, and the effect it had on the young artist. He described it as like the weird epiphanous insights that come to one on a strong LSD trip, a truth revealed that’s almost religious in its intensity. But then as the high wanes, what seems like a newfound addition to the human sensorium—this keenness of vision and feeling—disappears. “Only,” according to this person, “Crumb didn’t forget.” That’s the part of the longer quote that’s been sticking in my craw all this time, the part that I actually do remember word for word. “Only Crumb didn’t forget.” It plays over and over in my mind, taunting me when I write knowing that I’m only accessing a portion—a small percentage—of some great storehouse of power. I’ve glimpsed the full power in dreams and it seemed to course through my veins in childhood, waning in pubescence, practically surviving now only in the faintest echo. Still, some artists seem to be able to induce this state whenever they want. To quite Baudelaire (we’ll get back to him in a minute), “Genius is childhood recaptured at will.” But my own access to the magic is rather marginal by comparison to those I consider greats, and its appearance is rare in general even among their cohort. Should I maybe take a shortcut in opening my third eye? Get a tab of sunshine blotter acid and blow the hinges off the doors of perception rather than continuing to knock politely? I’ve never done LSD, and my friend who’s done quite a bit says I shouldn’t. “You’re basically on a 24-hour acid trip. It might just make you normal.” But when I was young I used to smoke a lot of weed. These days, due to decriminalization in lots of places and outright legalization in others, weed has lost a lot of the allure as something illicit. Back then, though, sitting in the bedroom of the apartment I shared with my mom—towel stuffed under the door, bong in hand—it still felt illicit. Sometimes I imagined myself a sailor supine in a hammock in some quayside opium den, feeling that temporal displacement Lou Reed invoked when singing of that great big clipper ship. You know that strange feeling you get sometimes when incredibly stoned, the suprachiasmatic nucleus confused between day and night, feeling that you’ve somehow smoked a hole in time? I was already given to fantasy and the overdramatic, and I’d read some Coleridge and De Quincey and Blake, so why not indulge in some hop house idylls? Needless to say, it didn’t take much imagination to turn my bedroom in that high-rise to a berth on a galleon floating through a city’s harbor at night. We lived downtown and there were plenty of cynosures for my bleary eye; I especially enjoyed the way the neon bulbs on the “24 Dollar Motel” fritzed on and off in sequence. And the dirty red sidings in the railyard beyond that always made me winsome. Cincy isn’t quite the Rustbelt, but the hints of heavy oxidation were there, in broken windows and the sooty brick faces of crumbling buildings. Yes, it started a melancholy ache in the belly, but so does falling in love. When I got bored with watching the world outside the window, I would read comics (or even comix), read books, and sometimes even do some homework. More often I would play videogames, usually the more immersive RPGs that took me away from my depressing and quotidian existence. When you’re a mage leading your party through the dark forests, slaying kobolds and seeking the king’s castle, it’s easy to forget your real life misery. That you’re failing out of high-school, that your parents are still at each other’s throats despite the divorce having been finalized years ago, that you’re basically going nowhere. The weed did what it was supposed to do, brightened colors, sharpened sound, made the dull feelings in me keen again. The world felt animate, friendly, as if it had a secret and it were sharing it with me, and things previously inert were loosening, becoming alive. But then the weed wore off, and there was a feeling of depression again—not just depression, but betrayal. For the glimpse of an enhanced perception had tempted me with a small taste of what might be. I probably would have been better off without the knowledge that altered states exist, since they were hard to reach, probably impossible without substances (or so I believed.) And you can only afford so much and only such quality when your entire income consists of allowance money, especially in that pre-decriminalization era when it was more expensive. Still I wondered: Was the seeming insight always a lie, or did the drug offer a true glance into a realm that might accessible, and maybe by other means? Even now I do catch glimpses of something—enter a heightened state occasionally in the course of writing—but it tends to be ephemeral and elusive. Reaching that state—that Stoff—is never guaranteed, and even when I do reach it, it recedes quickly. The writer and philosopher Colin Wilson had a name for this faculty, the one we could obtain by chicanery like drug use or obtain honestly by hard work. Or, if not hard work, then at least by rousing ourselves out of the general lethargy in which so many intellectuals and artists sink, mistaking their despond for revelation. Wilson’s claim, again and again, in works as diverse as Misfits: A Study of Sexual Outsiders and Origins of the Sexual Impulse, is unvarying. And it simply boils down to this: the chance to ascend in consciousness is always there, and simply requires us to push through that initial inertia. That bit of calcified chitin that accretes layer by layer, day by day, convincing us that there is nothing really numinous, is a lie. That we are powerless and hopeless playthings of Lovecraftian cosmic malignancies, or absurd tangles of essence born of senseless existence, a la Sartre, is also a lie. Wilson called this ability to see through the self- and society-imposed fog Faculty X, and considered it the cornerstone of his own philosophical weltanschauung, which he called “Positive Existentialism.” He thought it had some uses specifically for ESP and more generally as applied to phenomenology, but also saw it as relevant to art and aesthetics. Those of a more religious bent might see it as a Blakean encounter with the divine ecstatic; or, if you’re of a darker disposition, an the encounter with the unholy, the Satanic, as in Crowley or Baudelaire’s formulation. Then again, Baudelaire’s idea that it would be worth it to sell one’s soul for one moment of divine ecstasy is far beyond anything I’m talking about here. A bad trip or a bit of post-smoking depression is one thing. An eternity in flames in exchange for one great moment’s insight or exquisite pleasure is quite another. Even Faustus wouldn’t have made that bargain. Wilson very much believed we’re all wrong in seeing this great thing as ephemeral and transitory, as something we can only catch temporarily via butterfly net. There’s no need to torment ourselves with glimpses of it via drugs, which show then remove the sight of it, fill us with a pneuma that quickly outgasses. Neither is there, like Yours Truly, a need to perceive this thing as something that can only be grazed with the hand after hours of frustrated toil. It can in fact be seized and wielded, provided one does so with a modicum of grace, without too much brute force. Imagine it as more like trying to approach a fawn in a clearing than trying to win a prizefight. There’s simply a need for work and discipline, and discipline is just work that’s consistent in effort expended and time invested. In other words, work day after day, deliberate but not necessarily exhausting. Eventually, if we return to the wellspring often enough it can be relocated almost at will. I don’t think we can live in this magical place—outside of perhaps some very lucky and mentally powerful gurus and magi—but we can make the trip from here to there easier. And the less time spent getting from here to there, the more time we get to enjoy being there, before being called back; as, alas, must inevitability happen. We just need to try a little harder. Or at least, I do, That’s the theory at least, as summarized and related by one marginally successful writer on his ill-trafficked blog late at night. Good luck getting there for yourself.

0 Comments

Genre Brain: Some Reflections on Saving Cats and Pulling Ships Uphill

The other night a writer friend of mine said something that’s been sticking in my craw, ever since. I can’t remember the exact context of his comment, only that he complained that too many writers lately have “genre brain.” I didn’t press him too hard on what he meant, probably because I think I knew. The formulae popular in screenwriting—especially the more recent “Saves the Cat” beat sheet invented by Blake Snyder—seem to have replaced former formulae, like those of Syd Fields. Fields, for those who don’t know, popularized the concept of three-act structure. Some would claim that Aristotle in his “Poetics” pioneered the concept (and beat Fields by practically a couple millennia.) Strictly speaking, though, that’s not quite true, as Aristotle broke structure into two acts—consisting of complication and denouement—split by the triphthong-bearing peripeteia. My main objection to Aristotle’s method is that “peripeteia” is simply too unwieldy a word. After years of speaking German, Greek (as well as French) words seem to contain too many damn vowels to me. German probably has the opposite problem, with too many fricatives and glottal stops, but I’ve been speaking it so long that I don’t notice. Like the fish who’s been swimming all his life, I don’t know I’m wet or even what water is. As for my problems with Fields and Snyder, they may differ from my writer buddy’s in their specifics, but in general I think we have the same gripe. There is something stifling about this cookie cutter approach to the creative act. Where is the organic? The spontaneous? Why, when I try to write using this format, do I hear Bukowski’s old lament echoed on the wind, about the modernist writers he found so unsatisfying? “It’s a job they’ve learned, like fixing a leaky faucet.” If I wanted to fix leaky faucets, I would have become a plumber, and no doubt would have made more money with that than with this. Granted, wrangling feces from a toilet with an extended snake tool seems undignified, but it’s probably less humiliating than a long streak of getting nothing but form letter rejections. Yes, even after all these years, I still go months at a time without getting a “yes.” Those who prefer the hard-fast patterns of Fields—or the harder and faster dictates of Snyder—would no doubt object to my objections. “Who,” they might say, “are you to gainsay centuries of storytelling wisdom? Nay, eons of the stuff?” And they might have a point. If there is some innate storytelling drive in humans, some symmetry in well-told tales that we all respond to, what makes me think I can buck the trend? Indeed, if it’s all so innate—from cavemen painting mastodons on limestone walls to your uncle telling a dirty joke—why even try to fight it? Such a storytelling structure would be as much a part of our collective racial makeup as, say, fear of the dark. Such narratological devices as “the rule of three,” seem to hint that storytelling is in fact more science than art. Pit Goldilocks against two bears and the story feels underdeveloped, missing something. Add in a fourth bear and a fourth bowl of porridge and it begins to feel more quantitatively top heavy. How many times did Jesus claim Peter would deny him? Hint: it wasn’t two and it wasn’t four. Fine and well, then, but then why would Snyder or Fields insist on writing books on the subject? If it’s indwelling and natural, then what’s to teach, learn, or even remind ourselves by taking a look at a “beat sheet” just to give ourselves a refresher? I’ll stop with the rhetorical questions to point out a couple of things. First, one should always consider not only the source of advice, but the CV of the source. I hate to speak ill of the dead, but while Snyder (R.I.P.) may be regarded as master of popular diegesis, he also wrote “Stop! Or My Mom Will Shoot.” Besides that, his only other feature-length credit is “Blank Check,” a sub-Nickelodeon affair about a boy who comes into possession of a million bucks while running from the mob. Imagine taking the script for “Home Alone,” putting it into a blender with “Brewster’s Millions” and adding a rollerblading tween from a Sunny D commercial and voila! You’ve got “Blank Check.” I’m sure it entertained millions of kids at the time, and no doubt evokes nostalgic memories for those who saw it in its first run. But this is not William Goldman, who gave us “The Princess Bride,” and also gave us his own, very un-Snyder-ish maxim: “Nobody knows anything.” Getting to my second point, relying on the beat sheet is probably far more justifiable for a film than for a book. A film, after all, is much more collaborative, and thus at least some sort of barebones skeleton needs to be available to reference for all involved. The great directors—your Leone’s or Tarantino’s—might have the whole thing visually in their heads (and with Tarantino, the dialogue’s also in the ear). But the crew needs to be clued in, and everyone needs to be on the same page, literally as much as figuratively. Even a moderate-budgeted studio picture requires shelling out tens of thousands of dollars a day. Craft services for a writer is a burrito and a pitcher of black coffee (and a roll of toilet paper after that.) The logistics of feeding a bunch of people and lighting a set is quite another animal. Yes, a movie, unlike a book, requires money, usually gobs of it, even in this era of digital filmmaking and easy-to-use editing software. If I sit down in front of this computer and type a novel that ends up being a piece of shit, it’s no biggie. I can simply crack my knuckles, walk the dogs around the block, bitch and moan about being a failure, and try again. The only thing wasted is my time. It's completely different for a filmmaker. If a filmmaker creates an absolute piece of shit, they’ve not only wasted their own time. They’ve wasted the time and money of other people. They may, in the future, find it hard to secure financing for any other projects. There are no such limits imposed on a writer. You must secure no more money than is required to get a licensed copy of MS-Word or ribbons for the Underwood (for all you luddites.) Thus it makes sense for the Hollywood crowd to play it safer, since sometimes the rule—as disheartening as it sounds—is to play it safe or don’t play at all. Granted, there is a small corpus of roguish madmen and women—your Herzog’s, your Lynch’s—who are willing to pursue their visions over a cliff, if need be. But since any producer who gets involved with them knows this by now, they can’t complain if the thing only breaks even, or even loses money. Call it a prestige picture, write it off as an arthouse excess, and just make sure the capeshit tentpoles open big enough to subsidize the more rarified fare. That way Herzog can keep pulling boats over mountains and Lynch can keep unwrapping his plastic-covered muses as they wash from the rivers of his subconscious onto our benighted shores. This brings us back to writing, though, and away from filmmaking. To my friend’s railing against “genre brain” and my own concurring with his grievance. I think the dude was right. Not only that, I think, as a writer, with less to lose, you owe it to yourself to risk more. There’s something Willem Defoe said in an interview, some seemingly counterintuitive advice he gave that, in light of tonight’s post, now seems brilliant. “Try to fail.” Why not? There’s no consequence, and you can always hit backspace. Or, if the day’s work is really shit, hit CTRL+A and DEL and start over tomorrow. Or tonight. What else is there to do but get overwhelmed by the limitless number of choices available on Netflix, or to fall down a YouTube rabbit hole that starts with funny bloopers and ends with a two-hour documentary on the Illuminati that has you wanting to pull the fillings from your skull with a pair of pliers, lest “they” use the metal to send signals? No one will be the wiser, and you’ll be left facing that blank pixilated canvas once more. Ready to begin again, and maybe even succeed without the goddamn beat sheet. I’ll close with another quote, or rather a paraphrase, since I can’t remember who said it and thus can’t source it: A work of art can either be complete, or it can be perfect. There’s something that results from floundering, without recourse to a net below them when one’s walking the tightrope. Genuine moments of spontaneity, real surprises, can only emerge when you let them. Too many techniques tend to put the Muse in a straightjacket. How’s she supposed to favor you with her charms when she can’t even move her arms? Look at most of the best movies, and you’ll notice something. They have a messy, chaotic feel to them, a sense of unwieldiness, the pieces not quite fitting together. Apocalypse Now, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Once Upon a Time in America. Read about the troubled production histories of these films, the frustrations felt by the filmmakers, the roadblocks encountered, the feelings of despair. Guns were drawn, murder and suicide contemplated. But the work holds up, showing the pain and uncertainty were worth it.  Ensoulment: The Blessed Dead and Those Ensnared by Life Like a lot of people, I’ve tried meditating in order to reduce stress, calm my PTSD, and generally make myself healthier. Those who’ve done some meditation may have smiled wryly just reading that first sentence, because it contains at least a couple things wrong with it. A large body of the literature on meditation says that, when done correctly, there is no “trying.” Meditation is simply tuning into a process which is constantly running in the background for us (like a computer program.) The act of meditation merely involves rediscovering what is already there. If one allows themselves to breathe simply and naturally—through the belly as a baby, rather than through the chest, like a stressed adult—meditation happens. Or rather, it just is, waiting for you to enter it, like a river—or waiting for you to ride it, like an electrical current. Close your eyes, breathe, and start singing the body electric. Also, meditating for some reason, some goal—as if the universe were some partner in a deal from which a quid pro quo might be wrested—is fallacious. Done correctly (according to most modalities) there is no trying, there is just being, and in some cases, nonbeing. There are of course health benefits to meditation, of both mind and body, demonstrably proven in clinical studies. More than likely you’ll also observe positive changes in your life anecdotally if you do it and take it seriously. But in order for these benefits to be found they must not be sought. And since I’m starting to sound like a wannabe monk in his sand garden, dispensing paradoxical koans, I’ll stop. The point is that I’ve at least researched the subject (as much as any time-pressed, ADHD-addled Westerner might.) And I’ve tried (without trying to try too hard or too consciously) to meditate. And, as with learning to write or any other endeavor I’ve undertaken in earnest, I kept what worked, discarded what didn’t, and added some things. My technique at this point is about as syncretic as it gets, and is subject to further shifts, changes, additions and removals of certain aspects at any given time. “You never step into the same river twice,” and no meditation session is exactly the same as the last. That said, there is a throughline that seems to be beginning to appear in my work with the body and mind. For instance, I like to imagine that I’m dead. This sounds a little morbid at first, but it’s frankly the only way I can succumb to the present moment, to let go of unpleasant memory and future-related worry. I tell myself that I have died, that there is nothing to worry about, no light I accidentally left on in the house, no unpaid bill, no ringing phone. It’s the only way I can really get myself to unclench. I go through the entire cycle of death and decomposition while lying there, finding it soothing, at times even sublime. Usually it works better when I go outside to do it. I imagine my body not as some ghoulish skeletal vestige, but as a sort of compost heap where the animals can play and get use from me. I had “dominion over the Earth” for years, eating animals while feeling only the most modest pangs of conscience. Now, after adding my own carboniferous and microplastic detritus to Gaia’s clogged arteries, it’s payback time. Or at least back to the bottom of the food chain, with one less person contributing to the catastrophe of the Anthropocene. Despite being “dead,” I still breathe, and still have the basic use of my sensorium, which, in my faux death, has ironically grown stronger. I listen to the chirp of birds around me, the scrape of the squirrels clawing their way along the points of the picket fence. I imagine them coming closer than they actually do, taking tentative steps toward me, sniffing. Scurrying away and returning and repeating the skittish ritual before finally working up the nerve to land on my body and stay there. And, once that bold first bird or squirrel lands, proves this behemoth isn’t sleeping but is actually dead, the rest of the Lilliputians move in, en masse. Eventually the larger buzzards swoop down, peck out the morsel-like eye meat, strip the skin from my face, spear my soft belly with their sharp beaks. Then they return to the trees, or take to the skies with rashers of peeled flesh in tow. At that point, it’s as nature poet Robinson Jeffers put it: I ride along, enjoying my own “enskyment” (sic) as some piece of myself soars through the clouds. I’ll spare you the rest of my imaginings, as it only gets more macabre. Not every session is successful (again, that quid pro quo thinking), but sometimes the experience can be truly transcendent, liberating and seemingly without limits. Especially when the sun is shining but it’s not too hot, the birds are singing but the dogs in the neighboring yards aren’t barking their heads off. I imagine my soul leaving my body, the real “me” that is the actually me and not this husk with its face and its ego and its petty postmodern neuroses. Whatever was there before I was even a child, before I even was. It’s my return to some larger whole, an entity without number, a kind of giant glowing blue-hot ball of fire, a bug-zapper where the bugs willingly fly to escape being. I imagine it looking a bit like something I saw in one of those Pixar cartoons while hanging out with my neighbors and their kids. The movie was called “Soul” and (very briefly) dealt with a jazz musician who dies and must reckon with deep spiritual matters. Upon dying, the musician (played by Jamie Foxx) finds himself in a netherworld, a liminal kind of spiritual airport, a limbo between two worlds. It’s not as bureaucratic as the one in “Beetlejuice,” but in some ways it’s more disconcerting. There is a conveyor belt, almost like a cattle chute, which is leading the dead upward into a ball of what looks like blue ionized plasma. Most of those slated for reintegration into the big blue ball don’t fight it. And upon making contact with its corona, they seemed to evaporate, like bugs hitting a zapper. But the jazz musician fears that ultimate transmigration, thinking it might mean annihilation, an end of everything rather than the beginning of something new, a revelation and rebirth. This flight from the inevitable rejoining of the oneness, I think, is what accounts for so much restlessness during meditation. Eknath Easwaran described the mind as being a bit like an unruly, poorly-trained dog that can’t keep its eyes on the path before it where it’s walking. It wants to light after butterflies, sniff the butts of fellow dogs, chase that soaring Frisbee being tossed by frat boys on the greensward. There’s nothing wrong with wanting to live, to break from discipline and run free, but there’s a time and a place. And that’s most times and most places. This half-hour or hour of meditation is a gift you give to yourself, a reminder that needn’t be a memento mori, but usually is in my case. Sometimes while sitting there I wonder where we come from. “From an egg and a sperm” is the obvious scientific answer, which then becomes a zygote. We might trace our origins even further back, though, into the seminiferous tubules in our father’s testicles (which, believe it or not, include about two miles of plumbing.) All good and well, but how did we get there, into those gamete precursor germ cells, before even becoming tadpoles? And before that? You can do this forever, going back in an infinite regress, a why that leads back to another why until you have to concede, “I don’t know.” Science fiction author Theodore Sturgeon (who gave the world the phrase “Live Long and Prosper”) used to sign his letters and autograph with a strangely curlicued Q. It meant “Ask the next question,” and the one after that. Sturgeon was dealing more with challenging normative assumptions rather than questions of original generation, abiogenesis or the primordial soup where life first began, but his idea still holds. Follow the line of questioning back far enough, and the why can only be answered honestly by “I don’t know.” Even the hard science scribe Arthur C. Clarke conceded as much, with his quote that any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic. Start with a deist conceit that we’re all part of a clockwork mechanism created by God (or the Gods) and you get the same problem. The ancients believed in spontaneous generation, that maggots actually were born of rotten meat, rather than tiny eggs invisible til the microscope started revealing “animalcules.” They thought substances like wood contained “phlogiston,” which was released when subjected to fire, because they didn’t know about oxygen. The moderns laughed at this quaintness, until they tried to figure out how complex molecules and proteins were created from the “primordial soup.” Scientists conducted experiments to figure out how a world made of mostly ammonia and hydrogen eventually started to result in life. They managed, in lab conditions, to show how simple molecular structures gave rise to more complex ones, but these were only the “building blocks of life,” not life. We were suddenly back to the world of phlogiston and spontaneous generation, hypothesizing that maybe lightning struck the whole mess right and “something happened.” The spark was suggested to be an electrostatic charge, but it might as well have been a divine one. Most adults have experienced this humbling moment when a child, merely by posing one question after another, finally reveals this initial and ultimate unknowable Ursprung. The unanswerable “how” (forget the “why”) of getting from nothing to something, nowhere to somewhere. Comedian Louis C.K. even had a bit about it, back before he got really famous. The ancient Greeks had a concept for this appearing here, in this world, from the aether. They called it “ensoulment,” the moment where one is caught, or snatched from nonbeing (that big blue electric ball, if you will) and brought here. We tend to think of the one tadpole that reaches the egg out of the millions as the lucky one, the “lottery winner.” It’s the one that—through pluck, luck, or pure statistical mechanical law (something to do with tail length and motility) reaches the fertile soil of the womb. There, in the words of the Greeks (and in some Christian concepts) it begins to “quicken.” “Quickening,” is a bit like what happens to batter when it is stirred until it congeals, gains greater substance, becomes colloidal like mayonnaise, sort of existing in two states. Soon, though it goes from mostly liquid to mostly solid, though that baby will need water every day of its life and its blood is mostly saltwater. But this process of becoming, this “winning” doesn’t feel like winning when I’m lying there for twenty minutes, or thirty minutes, or an hour. When the simulated death starts to feel like real peace. Life and living and breathing and being start to feel like something else entirely. They start to feel like a snare that has caught my foot. Death doesn’t seem so bad when I reach this state. At least not my own death. If someone (a family member) or something (like my dog) dies and I’m still here, death will hurt like a bastard. But it will hurt me a hell of a lot more than it will hurt them, I think. Life and ensoulment and quickening, having a self, all seem like burdens in such moments. They all seem like temporal prisons, traps to ultimately escape. Looking at things this way definitely makes it easier to cope with the entropy my already half-broken body is enduring now: the pain in my shoulder; the arthritis; the waning sex drive and greying hair. I turned forty-two last month and “forty is ten years older than thirty-nine,” as Frank Irving Cobb once quipped. I’m not suggesting, however, that we all commit suicide in order to escape this world, or that we all become worshippers of Thanatos, God of Death. There are lessons to be learned from the agony of being, of desire. There are even lessons to be learned from self-inflicted suffering, drug addiction, gambling, sexual desire, which are really only attempts—at their most self-destructive levels—to reach nonbeing. To get that feeling of being loved not just by someone (pleasant) but by everyone who is also loving each other in some unseparated whole (euphoric.) Nor is life just a nihilistic and pyrrhic attempt to gain joy which cannot be gained. There is happiness to be had here, and victories, even though “[these] too will pass.” But honestly, for all I know there is no Big Blue Ball, and nonbeing isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. Maybe Joker’s right, that the dead only know one thing, that it is better to be alive. Gold Stars and Orange Pumpkin Stickers: Goodreads and the Never-Ending Grade School

Goodreads is a “social cataloging app” designed for booklovers to discover new books and interact with other booklovers. I use it primarily to keep track of the books I want to read. That’s an impossible task, but still, Goodreads gives me the impression that I might actually be able to manage or control my insatiable bibliomania. I also maintain an author profile on there, which lets me keep track of all the books I’ve written (some good, mostly bad.) Many of the anthologies and magazines in which my stories have appeared are also listed on the site, some under my profile and others not. Goodreads isn’t a perfect database, and sometimes authors with the same or similar names to mine find their way to my profile. I try to let the Goodreads staff know about this, but sometimes it feels like a losing battle and I let things stand as they are. I’m lazy that way. If people want to believe that, in addition to writing sleazy violent stories, I also write children’s books or medical texts, so be it. There is a famous social realist artist/painter named Joseph Hirsch and if you Google my name you’re more likely to get results related to him than me. His existence makes me regret not using “Joey Hirsch” as a penname, thereby sparing his estate the indignity of having his work associated with mine, if only inadvertently. Goodreads, in addition to having some good features and good intentions, has its sinister side, like everything else on the internet. Especially everything social media-related. A lot of what’s on the net is addictive by design. When designing their websites, apps, and services, many companies actually reach out to addiction specialists for help. Mind you, this help is not intended to make the services less addictive, but *moreso.* The features like notifications, the little messages that pop up, the bells and whistles, are stimuli meant to operantly condition users. They’re there to encourage certain behaviors—usually spending, but also engagement, so that one stays on the site longer, seeing advertisements and promotions. It’s also important to point out that Goodreads has been assimilated into the Bezos Borg, with all that entails. I spend a good amount of time on Goodreads but nowhere near as much as many others. Some people spend so much time on Goodreads it’s hard for me to see when they have time to even crack a book. Multitasking is the way these days, but unless one is listening to audiobooks, it’s hard to see how one could read while doing anything else. Does listening to a book even count as reading? Goodreads, like any other piece of media, risks falling afoul of the old Marshall McLuhan principle, with the medium becoming the message. And while literacy is usually good thing, it’s probably not good to get addicted to any website, even one meant to encourage literacy and mutual appreciation of books. The strangest two features of Goodreads have to be the Ratings and Followers features. For those users who aren’t authors, they probably haven’t seen the Author Dashboard. If you’re curious, you can google it to get a look at it. It makes sense that people should be able to rate and review books, to call them masterpieces or pieces of shit. They can even use the physical copies of the books as doorstoppers, as toilet paper (a la Castaneda’s Don Juan), or to organize their very own book burnings. It’s all protected speech, and once it’s out of the author’s hands, it’s frankly none of their business what the reader does. I personally never understood authors taking umbrage at harsh or critical reviews of their work. My relationship to my own work, (in case you haven’t noticed) is ambivalent at best. Additionally, like most people, I have my insecurities, doubts, and my own streak of self-loathing. Tell me not only that my books suck but that I suck, too, and—based on my mood—I’m as apt to agree with you as not. Not only will I agree, but I’ll probably amplify. In other words, anything vicious you can think of saying to me, I’ve crafted much, much worse words of self-wounding. I spend so much time in the editing and revision process that I typically end up hating my own books as much or more than my harshest critics. This is true for even the books I think are good, and maybe moreso for them. After all, I did sweat and labor more over the creation of the good ones than the bad ones. Usually, at least, that’s the way it works. Sometimes trying gives the work a feeling of flop sweat, while a casual approach makes everything feel more organic, less forced. Rereading anything I’ve written brings back the memories of the endless hours of proofreading, correcting, diagnosing problems of plotting and pacing. I worked so much on crafting certain passages that, like an actor who’s played a certain role many times, I can remember sentences and even whole paragraphs verbatim. I get nauseous upon reencountering them, like Alex the Droog after being programmed by the Ludovico Technique to upchuck at the sight of boobs or the sound of Beethoven. So, shitting on me is all well and good. The weird part of the rating system is that there’s an Average Rating aggregate displayed at the top of my Dashboard. Right now my cumulative rating is 3.84 stars. How bizarre is that? They have me rated, pegged, weighted down to the fraction, to the hundredth decimal place. Something about that feels absurd, unhealthy, weirdly specific. I’d frankly rather just be sat in a corner of some room wearing a dunce cap and given a “zero” or an incomplete as opposed to contemplating exactly what 3.84 means. It feels not just like a letter grade, but like some greater assessment of me, my Goodreads Social Credit Score if you will. Mulling this over is ridiculous, but it’s these ridiculous little things—subtle social pressures and cues—that tend to “nudge” our behaviors. It reminds me of the energy usage experiment conducted in one neighborhood. Those households whose consumption habits were under-normal received little smiley face cards in the mail; those who rated average in consumption received faces bearing a tightlipped, taciturn expression; meanwhile energy hogs got scowling faces with angrily arched brows. The cards did actually modify behavior, for the better, in terms of consumption. But what is the ultimate message, aside from that people—wanting to be thought well of—are very susceptible to praise or punishment? What, exactly is such a feature nudging me to do? Be a less shitty, less transgressive, more socially responsible writer? I suppose I could find some way to game the feature, pen a novel about a transgendered superhero (or even better, heroine) who battles transphobic supervillains. Pen body-positive panegyrics to overweight women of color. Or I could take the opposite tact, write manosphere tracts about lifting weights and eating elk meat and how to defeat women in the family courts. Decry “wokeness” like various grifters in the mainstream conservative movement, hit all the campuses while bilking the outraged, anxiety-riddled middleclass for their hard-earned dollars. I could also find some middle ground in the culture war, much easier to achieve if one is writing for children. All I’d have to do is steer clear of sorcery and the supernatural (lest some bible-thumpers classify my works as endorsing witchcraft.) I could write the text to a popup picture book about a boy who travels to distant lands every night when he falls asleep. That might get my Star Rating from the high 3s up to the low 4s, thus assuring me a larger dacha and loge seating at the opera house. In all seriousness, though, it’s weird to see that thing staring at me, those fractional stars (for lack of a better term) every time I log in. Film critic Roger Ebert once decried the “wackiness” of the star system he used to rate films, but he obviously found it a necessary evil. And this, remember, only required Ebert to traffic in stars and half stars, not weirder and smaller fractions like tenths of stars. What, I wonder, would he have made of a film that was awarded “3.84” stars by another critic? He probably would have concluded that the man was suffering from some weird form of obsessive compulsive disorder. Hasn’t the internet foisted that kind of thinking on all of us, though, wrecked our attention spans, our minds, and therefore part of our humanity? Reduced nuance, complexity, and ambivalence to a like or dislike. Swipe left or swipe right? Then there’s that aforementioned “Followers” feature we talked about. If I scroll down toward the right side of the Author Dashboard, there they are: little profile pics of men and women I don’t know, who don’t know me. What are they doing there? I rarely if ever have any interactions with them, and few, if any, ever like any of my status updates, whether I’m posting blog entries or book reviews. Most, if they’ve reviewed one of my books, haven’t reviewed others, so they’re obviously not following me from work to work. This is understandable, as I have trouble remaining in one genre for any length of time. I have a wanderlust about me that keeps me from writing series, or establishing a reputation for one kind of writing. What (or who) are these people following, then? Maybe they’re all automatically signed up after reviewing one book, or something like that. Regardless, the idea of having followers is especially bizarre for someone as antisocial as me, someone whose battery is recharged rather than drained by isolation. According to the widget, I’m up to 108 followers. I’ve been out of the Army for awhile now, so my concept of various troop size elements is a little rusty, but isn’t one-hundred more than a company? Isn’t it a bit closer to battalion in terms of strength? Should I summon the troops for muster and attempt to defeat another author on the Goodreads battlefield? And if my army defeats them, do I not thereby acquire their followers, thus assimilating them into my own army? Will the battalion not eventually become a brigade if I go from strength to strength, victory to victory? Or, if I’m of a more sinister bent regarding what to do with my suasion over my disciples, I could start a cult, hand out LSD-laced Kool-Aid laced. Wait for the acid to take effect and then address the wide-open third eyes of my now pliable acolytes. On a slightly more serious note, there’s something a little depressing, disheartening about all this. There’s an aridity to the knowledge that even in this—my one act of liberation from the constraints of society—I have somehow found myself fixed, assigned a grade. Smiling as some imago of a schoolteacher pulls the pumpkin sticker from her strip of paper and plants one in the center of my big ugly forehead. Or even worse, leaves my forehead bare, cold and naked, forcing me to stare around the classroom at the other kids, their brows shining with bright gold stickers. SWERVING ON THE SUPERNATURAL: SOME RUMINATIONS ON GENRE

Earlier today I finished writing a short story, tentatively titled “Last Turn of the Old Wheel.” Actually, I like the title enough that I can probably stop referring to it as “tentative.” I think I’m going to stick with it, when I submit it into the world for publication. Since talking about one’s work is only slightly less tedious than relating the details of one’s dreams, I’ll try to be brief in my summary of the story’s contents. It’s about an old man, who once was a cabdriver and is now housebound and cared for by his grandson. The old man is slipping into senility, but still retains enough of his faculties to mourn for all the things he’s lost, especially his erstwhile identity as a cabbie. To compensate for the old man’s sadness, the grandson gives him one of those racing game simulations, complete with a steering wheel, clutch, and pedal setup. His grandpa is happy, until the Gamestop where the grandson rented the equipment wants its console back. The place is closing down, and since the grandson is living on the poverty line, he can’t afford to buy a system. And since there is no other game rental store in the neighborhood, it looks like grandpa is going to have to go back to staring at the apartment walls. Until, that is, a techie who homebuilt his own proof-of-concept console offers his gaming system to the grandson, for a song. The kid naturally scoops it up and brings it back to his grandpa, presenting the currently morose man with the gift. Like most old people, the grandpa is reticent to try new things, especially since he’s still smarting from being forced to forfeit the old game system. Slowly, though, he begins to acclimate to the new one. It's not hard to do, as the new system is not only an incredibly real simulation, but centers around driving a cab around the city rather than something fantastic like street racing. All is going well, until grandpa gets into a “car accident.” The quotes are necessary, as the accident is confined to the virtual realm, and shouldn’t be a big deal. Except at the exact moment where the grandpa’s virtual avatar wipes out onscreen, a real wreck occurs outside the apartment window. Unfortunate coincidence, or something more? If you’ve seen enough “Alfred Hitchcock Presents,” “The Twilight Zone,” or read or seen any number of horror anthologies, you can guess how this might go. There are three basic options here:

This is an old problem, one which has existed in popular SF and horror for decades, as evidenced by my previous allusions to Hitchcock and Serling. Despite all they both contributed to popular culture, many of their showcase stories end up being too clever by half, especially in the last act. Especially with their overreliance on irony and the O. Henry twist ending. In Hitch’s case, this moment is usually accompanied by a few upward trilling notes on the flute. The main character might even break the fourth wall and look at the viewer when the dog digs up the wife’s body, or the plotter’s otherwise perfectly orchestrated villainy is undone by some minor bagatelle. The technique of the twist ending can be used not just to powerful, but profound effect—see both the “Alfred Hitchcock Presents” and “Twilight Zone” iterations of Ambrose Bierce’s peerless story, An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge. Most of the time, though, the viewer or reader can almost smell the flop sweat sliding from the brow of the storyteller as they struggle to write their way free of the corner into which they’ve unwittingly maneuvered themselves after two acts of tap-dancing. A great example of this is the film, I Bury the Living, about a cemetery caretaker who discovers he merely needs pushpins on a corkboard to kill a man. I won’t spoil the film’s big reveal here, for those who haven’t seen it. Suffice it to say, though, that horror maestro Stephen King is right when he says the film’s author would have been better off leaving the spooky source of the caretaker’s magic a riddle. Nothing about the mundane meddling that only appears supernatural in the runup to the reveal makes sense, when considered for any length of time. The film would have been better off going with option one or two. If one uses the unreliable narrator technique, the issue may never really be clarified. The source of the conflict might be mundane, but the narrator is crazy or superstitious enough to think it supernatural, or vice versa. Stephen King’s critique of Stanley Kubrick’s adaptation of his book The Shining very much hinges on a quibble of Kubrick’s swerving the supernatural. The book is very much about the supernatural explicable (King is a moralist), but Kubrick, an existential materialist, makes the story about the unreliable mental state of Jack Torrance. Since the guy playing Jack Torrance is Jack Nicholson, and Nicholson always looks batshit crazy, this works, at least for Kubrick and those of a similar Weltanschauung. There is of course another, final and fifth category of explanation (or lack of explanation), which I’ve heretofore overlooked. That would be the absurdity of the unanswerable, the inexplicable even by recourse to magic or handwavium. This is the kind of unresolvable resolution preferred by Kafka, by Dadaists, surrealists, and existentialists. These artists many times view consciousness itself as a trick, a cursed quirk of evolution that causes us to seek and expect solutions and sense from a universe under no obligation to supply them. The universe indeed might lack the consciousness we have, an endowment we either received from ourselves through solipsistic striving or some other freakish accident of egotism. This is where the lack of an answer at the tale’s end seems to suggest less the supernatural than the complete absence of anything extramundane or even something that can be apprehended with the laws of science. How or why anything happens can’t be explained away as being due to a spell, or hinted at as some kind of sorcery invoked in contravention to the usually obtaining laws, or even via some invention that widens human understanding and possibility to see the underlying laws at work. Recourse to neither Bible nor electron microscope, nor parapsychologist’s electromagnetic wand will reveal what is ultimately afoot. Some force is thwarting or Metamorphosing the character or their world—keeping them from reaching the Castle, putting them on Trial for unspecified crimes—to make a larger point about the remoteness or absence of any higher power, or meaning. There is no hope or explanation, only absurdity, and the only option is to laugh in the dark, alongside the dark, or have the darkness laugh at you while you weep and claw blindly at unyielding walls. Either find the funny in your plight or find yourself the butt of a joke whose teller might not even exist. Obviously this kind of existential, illogical surreality isn’t seen often in popular fiction, especially not on “Alfred Hitchcock Presents” or “The Twilight Zone.” I suspect such unsatisfying, resolution-free stories—free of climax and catharsis, full of frustration, lacking narrative symmetry—wouldn’t have sat well with advertisers. It makes a kind of sense, after all. For who the hell is going to be in the mood to buy soap or toothpaste or beer after having it relentlessly hammered home that there is no god and no hope? Or, as Kafka said, smiling, “There is hope, but not for us.” Aesthetic Theology: Or, How Leviathan and Behemoth Got Their Asses Kicked Political Theology is a fairly esoteric field, popularized by the German 20th century philosopher Carl Schmitt. Put in its simplest terms, it’s the idea that certain knowledge can be derived from religion and applied to politics and metapolitics. Schmitt’s main interest here was geopolitics, and how the megafaunal cryptids Leviathan (the sea monster) and Behemoth (the land monster) could tell us certain things about nations. Land-based powers like Russia were tellurocracies (Behemoths) and sea-based powers like the U.K. or U.S. were thalassocracies (Leviathans.) This affected how these nations saw themselves and the world and dealt with other nations. It also, especially, affected how they fought and what kind of wars they preferred to engage in. Nobody talks about Schmitt much anymore, partly because he was a member of the Nazi Party, but mostly because a lot of his stuff is very dense. It also helps to read Schmitt in the original German, and to have some grasp of Greek as well helps in the appreciation of his concepts like Nomos. Most people understandably have other, more pressing things to do with their time. I, not being most people—not having much of a life to speak of at all—can afford to think about this stuff. I can even afford to mull over if I might be able to derive my own secular philosophical insights from the Bible. Not being overmuch into geography, but still trying to give this writing thing a go, I’m more inclined to find aesthetic rather than political uses for the Good Book. So how about it, then? Aesthetic Theology? There’s a quote I found from the Bible. I didn’t stumble over it while reading the Good Book, (though I sometimes do) but rather while perusing another book I keep in my basement bathroom. This book is a collection of metaphors and aphorisms along with the author’s insights and ideas on metaphor’s contribution to thought and creativity. It’s cleverly titled Metaphors Be With You. The quote I stumbled across was on the subject of Humility. It came from the King James Bible, the Book of Matthew: “And whoever exalts himself will be humbled, and whoever humbles himself will be exalted.” What’s the relation of the above quote about humility to aesthetics, though? Isn’t the point of art to be the exact opposite of humble, to try to harness some Promethean fire and play God, if only figuratively in one’s work? The brilliant German philologist Bruno Snell in The Discovery of the Mind even argues that poets, in trying to praise their gods, discovered man’s godlike potential via linguistic abstraction. I think creation can be an exalting pursuit—and cathartic, and liberating. Likewise can it produce all kinds of negative feelings like frustration and inadequacy and jealousy at the skillset of one’s betters. But the best work, for me (at least as far as writing is concerned) seems to come from those who know how to subordinate their egos, to forget themselves. There’s more than one type of good writing. There is the kind of good writing that, as one reads it, they recognize as such. We read and feel how the writer was carried away in the throes of composition. We’re grateful for the pleasure of being able to ride along with them on their flow of words. Sometimes, if they’ve really caught a tailwind, their words can even surprise or please us enough to get a small physical reaction, a laugh or sigh. The buzz they achieve somehow becomes one they lend to us in that moment. Athletes call this state being “in the pocket,” and people in other fields sometimes refer to it as being in a flow state. It’s those moments we all work for, when the frustration and inadequacy and being tongue-tied or blocked or otherwise thwarted by fear or circumstance melt away. I’m reading a book right now by the journalist John Colapinto, which is very well-written, but consciously and meticulously crafted. All of its metaphors are well-chosen, never overextended, and when a big, seldom-seen word is introduced, it has an exquisite flavor, a perfection that feels unobtrusive. His style is showoff-y and calls attention to itself, but his skill as a wordsmith is undeniable. Words—which so often fail their users—become a malleable putty in this man’s hands. It induces admiration along with a twinge of jealousy to which I’ll readily admit. That so much of Colapinto’s book (and the previous novel I read by him) deals with jealousy only makes it all the more ironic and exquisite. This is a man who knows he has talent and knows also that more talented people exist, and that they experience their own agonies and insecurities, too. Having larded all that praise on Colapinto and his book, though, I have to admit that this kind of great writing is not my favorite kind. This is writing that exalts itself, and while it doesn’t suffer some kind of humbling defeat as a result, it has its limits, and its downside. This being conscious of the writer behind the work at all times—if only to admire him—keeps the characters and the world on the page at a remove. It reminds me of an old quote by SF writer Orson Scott Card, which I can only roughly paraphrase after all this time: You can either have people admire your words, or believe your story. Card further states that poetry is supposed to have its effect on the mind consciously, that it’s okay to actually read a poem and say, “Damn, that’s well-written!” Fiction is more often about achieving its ends through sleight, a dexterous subsuming of one’s urges to make their presence known, to receive attention. The clinging to one’s identity in the midst of creating characters (essentially other people, however fictitious) keeps the story from being fully transporting. This can work fine, mind you, and is actually preferred, if one is writing about the doings of their alter-ego. Author John Fante’s alter-ego Arturo Bandini and later Bukowski’s alter ego Henry Chinaski gain their reality partly by reflecting their creators’ desire for recognition. The desire to be recognized, to be praised—loved, seen, etc.—is a pretty natural one, and probably no sin in and of itself, assuming one believes in sin. Fante’s wife Joyce said that his greatest fear was to be known as a “‘Hey you,’ guy.” I don’t want to judge this kind of writing too harshly, partly because I myself am guilty of it, and often. Indeed, that my writing calls attention to itself is perhaps my main authorial flaw. What about the other kind of writing, though, the kind that, thus far, has been durch Abwesenheit glänzen, as the Germans say, literally “glowing through its absence?” This is the kind of writing that happens when the writer manages to subsume their ego as completely as a human can. These moments usually come when one is not concentrated on ethereal concerns like the Muse or mundane concerns like how the work will be perceived by readers. Such moments don’t just come with a buzz, but an eerie sense that some kind of veil that otherwise remains in place has been pulled back. The Muse isn’t just gracing you with her touch; she’s letting you peek up her toga. These moments usually come after writing “one word at a time,” as Stephen King so humbly put it in his memoir On Writing. It’s in such moments that the hands move across the keys like the planchette on a Ouija board seemingly shifting of their own volition on a stormy night. It’s scary, but it’s also sublime. And it seems to happen, for me at least, most when I “throw myself on the mercy of the court,” so to speak. When I start out writing slowly, pretending I’ve never written a word before. Sometimes I’ll even say the words as I type them, like a child phonetically teaching himself to read, unembarrassed and undaunted. Such moments of going slow allow me to exceed my usual hedonic limit of buzz to be had via composition. Rather than going from perhaps thirty to sixty, I get to go from zero to sixty, and sometimes all the way up to 120 mph. But it's only because I began in that spirit of humility that I get to feel that high. Sometimes at least. “Aesthetic Theology...” How about it? Maybe it’s total bunk. Or maybe it’s something to which you can add your own observations of how the Bible (or any holy book) impart not just moral lessons, but aesthetic techniques, too. Schrödinger’s Litterbox: The Internet, the Principle of Subatomic Superposition, and How to Kill Fewer Cats There are few scientific concepts as misunderstand or misrepresented as that of Schrödinger’s Cat. In fairness to those who fuck it up (myself included), it is a mindboggling concept. It only grows more mindboggling when one realizes it’s not just a concept or principle, but as real as gravity. I almost wrote “as observable” as gravity, but gravity is mostly observed by its effects, not by itself.

In the simplest terms, Schrödinger’s Cat is a way to visualize quantum “superposition” in a way that even the layperson can kinda sorta understand it. Superposition holds that the rules of matter are easy to understand provided we’re dealing with atomic matter. Get down to the subatomic and things get weird. A subatomic particle, in fact, exists in a state of superposition—both/and—until directly observed or measured. In other words, the subatomic particle is doing two things at once until the scientist actually takes a look at it. In real life, a cat trapped in a closed box where a boobytrapped phial of poison may or may not have been opened is either dead or alive. The idea that it’s both alive and dead until its state is observed or measured is supposedly just an atomic-sized metaphor for subatomic particle behavior. In the Coen Brothers film A Serious Man, about a physics professor having a crises of faith, he explains it to his student one-on-one thusly. “The cat is just a model for the math. The math is what’s real.” Not to mention important to the kid’s grade. “Even I don’t understand the cat,” the professor says. There’s a problem, though, with pretending the cat is just a model or metaphor, rather than existing in superposition itself. If you put enough subatomic particles together, you get particles. Put enough of those particles together and you get matter. Whether it’s organic or not is a matter of chemistry. When exactly subatomic particles behave as particles touches on the concept of flocculence. This is particles aggregating to become bigger things and is best understood by engineers with a strong gasp of good old-fashioned Newtonian physics, i.e. an apple that either falls from the tree or doesn’t. Trying to figure out when a bunch of “little things” become one big thing—or a bunch of little things is also one big thing—touches on the Sorites Paradox. That’s philosophy. But you see then that the cat being both alive and dead is in fact, not a just model. It’s just a question of when its reality becomes observable to us, and how. Turns out the professor in A Serious Man wasn’t being humble or facetious when he said he didn’t understand the cat. He was simply wrong in seeing it as a metaphor for the math (or rather, the Coens, like most people who touch the subject, were wrong.) The cat only becomes one thing in one state—alive or dead—after being observed or measured. And yes, hearing the cat meow or the scratch of its claws against the inside of the corrugated box counts as measurement. It’s at this point that even the biggest of big brains disagree on exactly how many cats there are, though. Or whether the cat you observe—dead or alive—is the only one left of the original two. Nobel laureate Niels Bohr believed in collapse of the wave function, a thing represented by this cool little pitchfork symbol, 𝚿, which is just the Greek letter “psi”. Once you opened the cat’s box and saw whether or not it was alive or dead, you turned the superposed cat into a single living or dead cat. At least according to Bohr. Congratulations, you’re a magician. Another scientist though, named Hugh Everett the Third, claimed that it only appeared you and your eyes had collapsed those two cats into a single one. Rather than collapsing the wave function, you were simply riding one of the propagated waves. It appeared to collapse because you are just one you at a time. The you who opened the box and sighed with relief to see the cat hadn’t tripped the poison mechanism is just one of you. Another you (with whom you’ll never interact) opened the box and saw, much to his horror, the little butterscotch tabby curled up, lifeless in the box. This other you turned out to be a shitty magician and should also seek therapy from the resulting guilt and trauma of poisoning a cat. Who, then, among the big brains is right and who is wrong? For a long time, most people thought Niels Bohr was right and Everett was wrong. Partly this was because they knew about Bohrs’ theory, as he was a well-established and well-funded, much celebrated Nobel Laureate who enjoyed institutional support. “Everyone,” as the currently en vogue Bin Laden once observed, “loves a strong horse.” Meanwhile Everett was just an ill-mannered, chain-smoking young man whose doctoral thesis faced many challenges. He was prickly even among a normally contentious and prickly group of (mostly) men not known for observing the social graces. As his academic career floundered and his papers moldered in some Harvard subbasement, he became even harder to deal with. He drank heavily and did R & D work for the military industrial complex, and the secretaries he sexually harassed claimed he had bad BO. He had a couple kids, too, one of whom committed suicide, and another of whom is the lead singer of the popular indie band, Eels. Scientists, despite the cosmic scope of their remit, can be petty, vain, as given to the picayune vagaries of human emotion as anyone else. Academia is a cutthroat Machiavellian world where resources like tenure and grants are scarce, and fought over more tenaciously than rare oases discovered in the desert. I only survived to get an MA, and every moment I spent on-campus I felt like I was suffocating, my ribcage contracting until my chest hurt. And if Everett were right, he was basically putting his cigarette out on Bohrs’ addlepated skull. Not only that, but scientists would have to contemplate the deep philosophical and moral implications of a multiverse, not because they wanted to, but because the math led there. With the passage of time, though, Everett’s theory has come to be not only accepted, but embraced by many, and not just hack SF writers like yours truly. To those who don’t have to bolster their supposition with mathematical proofs—i.e. artists, screenwriters, philosophers—Everett’s idea is the more interesting, the more savory. Its implications are definitely more metaphorically resonant, too. Just remember that the cat isn’t a metaphor, though. The cat is a model for a reality, whether you think that reality consists of branches or a single line. It’s only metaphoric to the extent the metaphor lets you visualize what you can’t understand when written out in equations that span multiple chalkboards. If you’re the kind of person who quails before math problems that involve Roman numerals, you definitely have no business getting near the ones that need Greek letters, too. Be thankful for the cat. For myself, the model-metaphor involves another box, and rather than a cat, a man. The box in this example would be the computer screen on which these words are being typed, and the man would be me. Sitting here, now, I can sense (but obviously not see) the various branches I could take myself on just by typing. I could write a well-written sentence or a shitty one. I could potentially close this MS-word window out now—without saving this document (no big loss) and search the dark web for guns and pills. The fact that I’m even thinking about it (or at least facetiously countenancing it) means on another branch there’s probably a me already doing it. This me is either soon to have an Uzi micro and a prescription bottle of Perc 10s in hand, or is soon to be cuffed by an ATF agent. Sometimes just thinking about doing something, I’ll feel a little breeze, or at least imagine I’m feeling one brushing past me. Is that me going off on another branch, I wonder, succumbing to the impulse there while the more circumspect me remains here, riding this spear? If I reconsider again, and cave to the urge—especially if it’s sinful or ill-advised—I’ll feel the wind again, probably because I’m hopping onto another spear. Call the personal computer hooked up to the net Schrödinger’s Litterbox, then, a kind of container that’s only as pure or dirty as the creature using it. Some use it to read scholarly articles on the latest development in crater-sited coronagraphs and its implications for direct imaging astronomy. Others use it to watch BBWs wrestle in kiddie pools filled with vanilla-flavored custard. Some—sui generis renaissance men—like me, do both. IN THE BELLY OF THE BOOMER: OCTOGENARIAN ARCHETYPES AMONG USI try not to write about politics, even in these throwaway blog entries.

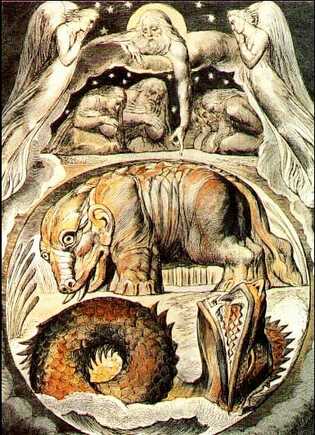

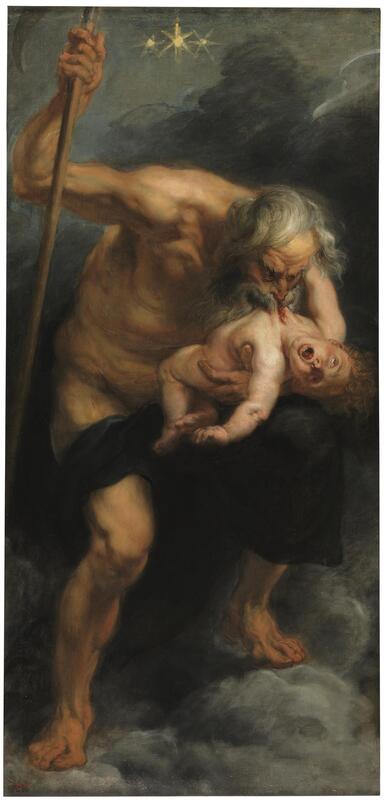

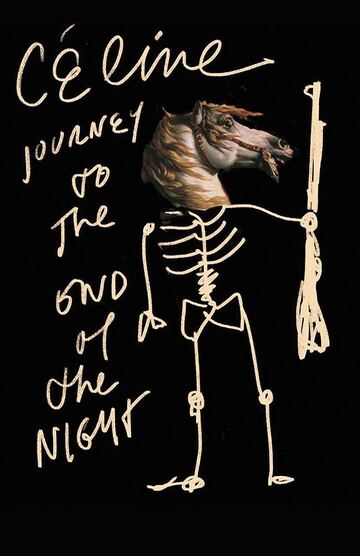

And still, sometimes I find myself dealing with the political, if only the metapolitical, and how narrative structures that appear in art also appear in life. I won’t club you over the head with a recapitulation of Joseph Campbell’s various archetypes and their shadow selves. If you’ve ever seen a Star Wars movie or a Pixar movie, or played a million different roleplaying games, you’ve encountered this stuff. Suffice it to say that most works that mine Campbell’s “monomyth” usually stick to the Hero’s Journey. This follows a protagonist on their arc from a sheltered youth to a reluctant fighter for some cause. They grow into someone—who through trial by fire and aided by a wiser, older figure—reaches adulthood, having passed various tests and found their mettle not wanting. Notice, in that rough thumbnail description, that seeming throwaway bit about the “older figure.” This is your Merlin, your Yoda, your Mister Miyagi, the sage who must train the impetuous youth for their ordeal. The Wise Old (Wo)Man has their work cut out for them, as the young person is so eager to right various wrongs that it’s hard to teach them anything. And they need a crash course that will at least give them a fighting chance, if nothing more, when facing an incredibly powerful foe. This foe, of course, is the shadow archetype of the benevolent wizard, the sorcerer to his mage. What about after the young hero slays the dragon/evil king, emerges from their katabatic journey into victory? Do they rest on their laurels? Live “happily ever after,” stroking the golden fleece they liberated from the hydra, or having babies with the princess they saved from the wicked sorcerer’s enchanted keep? Presumably, they become a wise old king themselves, enjoying the fruits of their labor, the spoils of war. Their hair grows grey, their beard grows longer, and they watch their grandchildren wander around the throne room, the kingdom finally at peace, at least for a time. If there’s one thing a story can’t stand, though, it’s stasis. Even the old must finally change. That means it’s time for the hero to assume the role of wise old man. He must, as Yoda once counseled, lose everything he fears to lose, in order to grow. He needn’t just drop his crown and head off to the woods to fashion himself a woodland hermitage made of sticks and mud. Nor must he retreat to the mountains and begin quarrying rocks for a cairn to heap upon his own grave. It needn’t be so dramatic; he can even remain on the throne for a time, as long as he is training the next generation to assume control. But what if he doesn’t do this? What if he refuses to recognize that his time is nigh, that some foes (like mortality) not only shouldn’t be fought, but should actually be embraced? Just as the hero can refuse the call to action—succumbing to the shadow archetype of coward—the old man can reject the final transformation that comes with death. If he refuses this ultimate transformation, he becomes the inverse of the archetype to which he has dedicated his life to instantiating up to now. He becomes his shadow archetype. Rather than seeing the next generation as his rightful heirs, he sees them as potential usurpers to his throne. Like the ancient dowager in an old Alfred Hitchcock Presents episode, every time he hears his grandchildren laughing from the other room, he thinks they’re plotting his demise. He may be dependent on them to prepare his meals, but he’s also convinced they’re poisoning him so they can get their inheritance faster. As for the approach of death, the Sorcerer doesn’t see it as the natural coda to life, something which should make him grateful for the great respite. This is not the old bluesman’s “burden” to be laid down, when all hard trials are over. He has grown accustomed to life’s pleasures, ensconced in his castle where the pain can’t get to him. He may begin to think about the catalog of his sins, and greatly fear that he may have to pay for them in the afterlife. Conversely, his faith in whatever religion he espoused throughout life may be waning, or may have always been a front, and he fears the eternal void. He is bitter, and rather than viewing death as universal, he anthropomorphizes it. He personalizes it, claims it is picking on him, shouts at shadows like Scrooge hiding his face beneath the bedspread and urging the ghosts begone. Fear of death and pining for one’s lost youth are natural emotions. It’s when the Sorcerer begins casting about for a way to escape Death’s clutches, and begins bargaining, that things get bad for him. If he succeeds in conjuring the Devil—or Mephisto, or the Dark Side of the Force—he will sign a deal written in blood, in exchange for his soul. What does he get? More life, or even eternal life, in exchange for allegiance to this evil which promises to bend the rules for him. He may even need a sacrifice to give in exchange for this gift; it may even be the hero themselves. Think of the way the evil Emperor in The Empire Strikes Back used Darth Vader as a kind of helpmeet to lure Luke to the bargaining table. Or the horrific (and hopefully apocryphal) story of Pope Innocent VIII drinking the blood of three young boys on his deathbed in a vain effort to gain their lifeforce. I bring all of that up now to get back to my original point: I try to stay away from politics, even in these blog entries, but sometimes it’s hard. Especially when that politics is metapolitical, and it goes so far as to even touch on the mythopoetic. Right now America’ s ruling class is top heavy with geezers. I’m not the first to note that we’re living under a feckless gerontocracy. It’s also obvious that while many of us lack conviction, the worst of us are on twitter, filled with passionate intensity. And that contingent usually consists of shitlib boomers like Rob Reiner and Stephen King, sanctimoniously claiming the moral high ground and demanding the rest of us fall in line. There’s no question, that in the time of covid, their cohort was hard hit, and they certainly have as much right to their feelings on the subject as anyone else. It’s also certain that if the disease had wreaked havoc on the young and healthy, we wouldn’t have seen the nationwide hysteria and disruptions we were forced to endure. The Boomers are so used to being the fulcrum upon which the world turns—the cynosure of everyone’s eyes—that we were required to shut down society on their behalf. It’s no surprise or coincidence that Lysenko-like apparatchik Anthony Fauci was a Boomer, or that Trump, arrogantly touting his efficacious “warp speed” vaccine, also hails from this cohort. And on the subject of Trump, their monomaniacal obsession with him has become, as comedian Kurt Metzger pointed out, a bit like Ahab’s suicidal quest against the White Whale. I’m convinced that if these Boomers were faced with incontrovertible proof that a second Trump term might’ve averted war over the Donbas, they wouldn’t care. A man who offends them viscerally but might have spared a few hundred thousand lives just isn’t worth it. They’re only concerned with harpooning him from the heart of their very own self-made hell. If you have these obsessive Boomer types in your life, you know they don’t care. They don’t care that the coterie of advisors surrounding the Child Sniffer in Chief has brought us to the brink of nuclear war. Nor do they care that America’s borders have become so porous and dysfunctional that even the most xenophilic progressives are starting to quietly, privately, grow uneasy. In a way, it makes sense that the Boomers would be more reticent to admit their time is over than previous generations. The Silent Generation and Greatest Generation before them generally had much harder lives. Youth culture and the concept of a teenager didn’t even exist in their day. It was a result of postwar mass affluence that touched even the working classes. The Boomers were doted over, studied as a cohort, fretted over when they flirted with juvenile delinquency. They were catered to in the culture and in the music and told for decades that they and their heroes and historical figures and their wars were the most important thing in the world. They mocked the aged of their own day and hubristically declared that they themselves would never get old. And as they grew into institutional power, those same Boomers who regarded the Vietnam War as unethical became neocons and supported what amounted to genocide. It was a genocide, by the way, that Trump publicly decried, in South Carolina, the supposed home of the most rabid and warmongering among us. Jim Morrison only got it half-right in Five To One. His generation has the guns and the numbers. And it has hurt them greatly. They can’t admit to the human condition, age gracefully, admit, even into their eighties, that they are no longer teenagers. Nor can they admit that they’ve deliberately selected their replacements (in politics and everywhere else) for their fecklessness. Their fear of being usurped has ensured that anyone who comes after them is too incompetent to even administer the state or govern correctly, even if they wanted to. I believe it’s this fear of death—a death which was much less hidden and better understood in the days of generations past—that caused their apoplexy over covid. Death is terrible, and that the aged can be killed by a flu seems unjust. But the solution to this problem is not to lock children in their homes, isolating them so that not only their immune systems, but language acquisition and facial affect reading skills suffer. To do that is to behave as Cronus in Greek myth did, or Saturn in his Roman derivation, to swallow one’s child in the attempt to hold back time. Tying this back into Campbell’s taxonomy, it’s important to note that not everyone hits every one of the arcs, from the hero to the mage. It isn’t just a matter of ageing through the various stages of herohood. One must make the right choices, take rather than refuse the calls to action, lest they become in some way stunted. I could speculate on what makes our rulers so immature, what rites of passage they shirked in order to become such mockeries of sages in their declining years. Maybe it was the draft deferments—the five Biden got for asthma, the who-knows-how-many Trump got for bone spurs. But I’m done speculating for now, and done with this unsavory subject. Suffice it to say that even calling these gormless old men evil is to impute too much depth and nuance to them. Biden is not Emperor Palpatine, standing before the threshold to eternal darkness, tempting the Hero to make the same Mephistophelian bargain he made. He can barely stand up, or go two minutes without flirting with the nearest twelve year-old girl in the audience unfortunate enough to endure his withered gaze. And his son’s an influence-peddling crackhead whose penchant for recording every moment of his perfidy means not even the most nimble twitter-fingered Boomer can hide the truth. Which is that, when they look at Trump they see themselves, and that is why they hate him so. A Biscuit Tin Full of Tears: Rereading Ferdinand Céline’s |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed