THE CELLAR IS THE SAFEST PLACE! THE ZOMBIE George A. Romero is one of my favorite directors of all-time. His most fruitful period was undoubtedly the time between the creation of the first and second entries in his Dead series, Night of the Living Dead and Dawn of the Dead. That’s not a large timespan, but one cannot overemphasize the man’s influence on the genre specifically, and on our culture as a whole, within that relatively short time. He struck a primal chord with his films, like Steven Spielberg did with Jaws, but what Romero did was not just primal, but political, and personal (to bowdlerize the old quote about the personal being political). A human being getting bitten by a shark is actually a kind of rare occurrence, and the misconceptions (or perhaps misapprehensions) that Jaws fostered were something that the book’s author Peter Benchley later lamented. Also, it’s nothing personal. A shark’s a different species altogether.

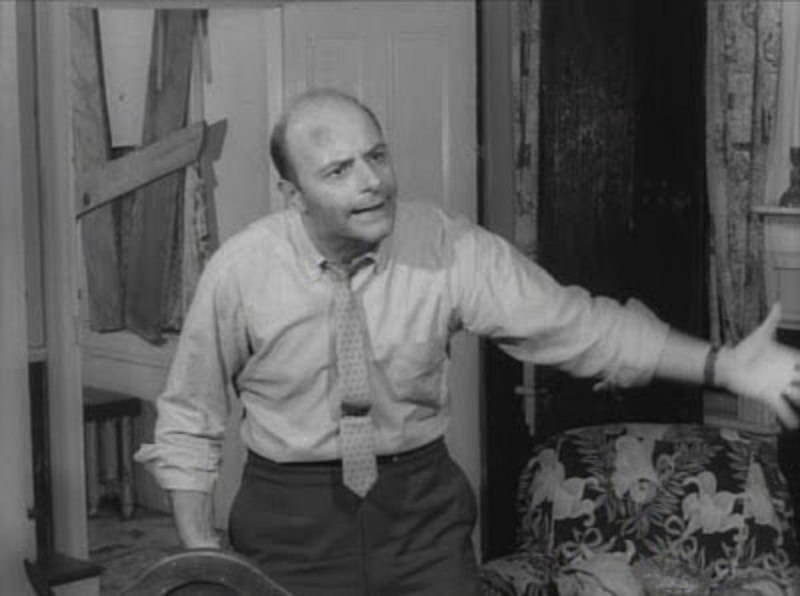

But getting bitten by a human, getting devoured by a person (even a former person that’s arguably no longer technically human), that’s not only primal but it’s a major violation of all kinds of taboos. The real heart of Romero’s Dead movies, though, and their genius, is that the focus is as much on what the humans do to each other in crisis as what the zombies do to the humans. For large portions of both Dawn of the Dead and Night of the Living Dead, the undead exist mostly offscreen, either stymied by barricades or trapped behind big-rig trucks that have been parked to deny them egress to the mall where the warm-blooded are dwelling. And these parts of the zombie movies without the zombies are the most compelling in some ways (though it is fun to watch the humans get disemboweled, eviscerated, and devoured by the vacant-eyed shufflers moving around in their pancake makeup). Romero once confessed that he actually viewed the zombies as the good guys, or at least the unwashed masses who would inevitably overrun the tiny minority of still warm-blooded humans (the third film in the series, Day of the Dead, actually gives a rough estimate of the ratio of zombies to humans, and it’s obviously comparable to what today we would refer to as the 1% vs. the 99%). I don’t want to get too deep into the weeds here, or veer into some Film Studies analysis that drains the movies of their charm and magic just to show off my useless degree, because the truth is that the only reason we still think about these movies and talk about them is because they work in all the ways we don’t need to think about or talk about, manipulating our fears and heightening tension (and going for the Grand Guignol gross-out when necessary). But to at least pay the imago of my professor some lip service, it’s worth noting that the first Dead film does a good job of distilling the conservative and liberal mindsets down to their Manichean essentials. In brief, in Night of the Living Dead, at one point an older couple and a younger couple find themselves trapped in the house which the zombies are attempting to besiege. The older man, Harry Cooper, has a classic door-to-door salesman vibe to him, the balding pate, the sort of cynical hard-ass look of someone who resents everything in his life yet insists his offspring mimic his path, because it’s “respectable.” The younger kid looks a bit like he’s on the verge of being a hippy, just clean-cut enough to still fit in with the Johnny Unitas crewcut set griping about desegregation, but he “needs a haircut!” (to quote the old heckler’s chestnut) and is perhaps eyeing those people and that town he grew up in a little askance now, and with a longing to get away. The kid’s name is Tom, and his girlfriend’s name is Judy (Romero’s films have some interesting things to say about feminism, too, and women in general, but that’s collateral to the point I wanted to explore here). Tom finds himself gravitating to the leadership of Ben, another survivor who made his way to the house with Barbara, a mostly catatonic blonde who earlier saw her brother murdered by one of the undead when he was going to lay a wreath for their dead mother in a cemetery. Ben’s a lithe black man who exudes the kind of precarious pride that someone like heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson represented (or perhaps Sidney Poitier is a better analogy). His behavior, his very existence, makes denying his humanity prima facie absurd, and there is something about his quiet dignity that pisses off racists more than the kind of blaxploitation über-pride of a sex machine Mandingo, who, despite his defiance, is sort of a parody of himself and thus seen as less threatening (though obviously in the most literal sense, a Sonny Liston can not only kick your ass, but kick it much easier than a Floyd Patterson). Ole Harry, oozing his Willy Loman flop sweat, insists that “the cellar is the safest place!” repeatedly. And since he has a daughter already down there (who was earlier “bitten by one of those things”) it would make sense to hunker down underground and wait for the zombies to pass upstairs through the house, where, presumably they might eventually meet their end at the hands of roving hillbilly militias or to some deployed National Guard units. Tom, however, forms an alliance (to use a phrase for the reality TV generation) with Ben, and the twosome remain adamant against the old man, who eventually tyrannizes his wife into acquiescing to his demands to go downstairs (sort of), while the youngsters decide to continue to wage the good fight aboveground. Spoiler alert: Things don’t go well for Harry. I mean, sure, everyone dies, but the old folks who clung to their calcifying and cloistered world of the past, down below, face an especially ignominious end. Dad, already gut-shot by Ben in an early dispute, slinks down to the basement and collapses by his ailing daughter’s side. She shows her gratitude by feasting on his corpse. Mom meets her own similarly gruesome end, getting stabbed to death with a trowel by her infected, now-reanimated daughter. Throw in whatever kind of Freudian stuff you want about patricidal and matricidal fantasies, and then leaven that with a smattering of rehashed observations about how this is supposed to symbolize the Woodstock generation rising up against their parents to establish a new order. But there’s something else, though, something interesting and worth noting, which I had meant to get to earlier: I usually eschew writing too much topical stuff, even when just thinking out loud, like in this blog, but isn’t it curious that, amid the C_vid-19/W_han Virus outbreak, the trend appears to be that the conservatives and liberals (again, generally) have staked out territory in the overall argument which is the exact opposite of that instantiated in Romero’s grainy old masterpiece of a horror movie? Donald J. Trump wanted to lift the lockdown that has America (and much of the globe) at a standstill. The fear from this camp is that the potential economic depression which might result from “flattening the curve” in terms of halting the virus will eventually interfere not only with the Dow Jones and your 401K, but other little issues like getting insulin to diabetics or food on your table. “Herd immunity” is also a term that has been bandied about quite a bit in some circles in counterpoint to curve flattening. The other camp, however, mostly (but not solely) composed of people who despise Trump and would consider themselves generally liberal on a L-R axis, think that hunkering in place, the continued closing of schools, and the eschewing economic concerns as ancillary is the way to go. They’re not literally in their basements, but “Flatten the curve!” has become their mantra, a fugue-like refrain, and the initial idea that restrictions might be lifted by April 3rd (today, incidentally) was greeted by these people the same way Harry might have responded if Ben or Tom suggested that perhaps if everyone took one bite on the arm from a zombie they might build up an immunity to zombification. It’s easy to understand why the poles became inverted on this one. The redneck-bumpkins in Flyover Country who thought borders were good last week don’t live in dense urban centers where the horror stories about running out of space to keep bodies has sobered quite a few of the good cosmopolitan people to the reality they’re facing, and despite all their earlier tough talk about trade wars, the gun-and-bible-clinging hillbillies have discovered they do in fact want to keep getting some of their cheap crap from China. Conversely, those pussy-assed liberals in blue cities who were talking about the wonders of diversity last week, especially emphasizing the wonders of the cuisine, might suddenly be wondering if eating bats is a good idea, or if borders (or at least the idea of limiting trade with China) is all bad. Yes, we are finally seeing the world through the eyes of our enemy, forced to concede (whether left or right) that there is some merit in staying on the first floor, using fire pokers and whatever other improvised brickbat is handy to beat back the clawing fingers of the zombies peeking through the boards over the windows; or conversely, that maybe sometimes the right thing to do is to hide in the cellar, stay there, and let the foul wind pass you by. And all it took was the impending potential for the total collapse of civilization for us to make these meager concessions. I’m proud of us. Look, this could be a temporary blip and we might see a reset by summer. I’m not advising anyone to strip naked and walk through the middle of the street reading loudly from the Book of Revelations. I’m not saying I have the answer, or which group is right, because I don’t know. I am neither a virologist nor an economist. But there is at least one thing I can say with some measure of certainty: Night of the Living Dead and Dawn of the Dead are damn good movies. It’s hard even in the genre of fantasy to build a world people want to inhabit and return to again and again, and the genre of fantasy is one primarily purpose-built for world-building. Horror is usually much more elemental, and in some ways elementary, focusing on chases and chills, and yet here we are talking about a movie made more than half a century ago for less than the catering budget of most movies being made today. There’s some comfort, and perhaps even inspiration, to be taken from that, regardless of what happens with this virus and what happens with us soon. We’re pretty resourceful when we want to be, or need to be. Or at least we used to be. I haven’t seen a movie as good as Night of the Living Dead in a long time. And I’ve yet to see anything as inventive or brilliant as Dawn since I first laid eyes on the thing when I was twelve years old.

0 Comments

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed