A Guy getting Shot in Sarajevo can screw up your Sex LifeTraditionally human beings have regarded the history of events as worth documenting, and history’s effects on the individual as much less worthy of note. Most of the time the individual’s role in history was typically confined to the principal movers in the conflicts, say, a Caesar’s recollections about a campaign against some enemy of Rome. Readers in previous ages were obviously aware that individuals were fighting in these setpiece battles, but to read of the account (or even stranger, the personal terror) of some lowly hoplite or spearman in a phalanx would have struck them as bizarre. Why would you want this “worm’s eye view” when it will give you very limited details about the topography of some conflict? Surely a general’s account or even that of some aide-de-camp would be far superior.

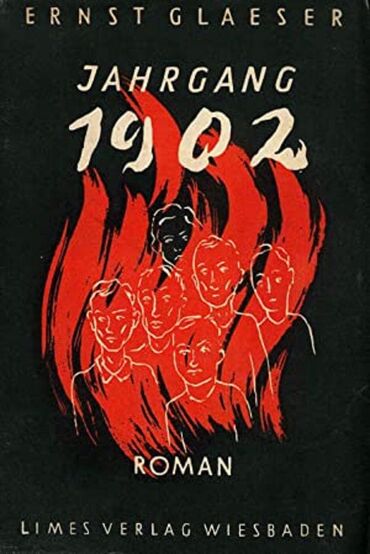

This started to change for a lot of reasons in the late 19th and early 20th century. This is just an ill-trafficked blog (and I just woke up and the coffee hasn’t quite started to course through the veins), so we won’t go through those reasons tonight in any detail, but just to count a bit of coup: Humanity as a whole became more literate over time, and access to both learning to read and the printing press meant that classes previously unable to articulate much of anything had more time and resources to do so. Also industrialization and advances in weapons technology started to give even the most martial of minds the heebie-jeebies about men being the playthings of their weapons and not the other way around. A man wielding a sword against his foes is the star of the show. Someone sitting behind a caisson and limber in the rear and stuffing mortars into a tube is a mere subaltern to the cannon he’s manning. One might be tempted to add that nascent philosophies such as humanism also changed the focus from what the general saw to what the grunt felt (or what the civilian whose hut was in the way of the shell suffered), but I’m not quite sure about that. Young Paul Bäumer in Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front is undoubtedly a humanist, a disillusioned soldier and budding pacifist whose world is mostly an interior, private rebuke of the Weltanschauung in which he was steeped from birth. But the deeply pro-war, perhaps even war-worshipping, diarist Ernst Jünger was every bit as fiercely inward-looking and individual-obsessed as the compassionate humanist Bäumer. Jünger’s early fascist leanings didn’t keep him from being as solipsistic in his view of soldiering as any tortured teenaged diarist filling up a moleskin diary with her thoughts, observations, and feelings. You can of course find exceptions to the rule occasionally cropping up even before the modern era, books more concerned with how historical events, especially wars, can ruin an individual life, as opposed to how they change the course of the world. Jakob Grimmelshausen’s Simplicius Simplicissimus is a seventeenth century book by a man and about a boy who both view the Thirty Years’ War as a senseless intrusion onto the lives of individuals who have much better things to do with their time than kill or die, things like read, make love, drink wine, wander around in mummers’ bells singing funny songs, et. al. I’m probably not telling the reader anything they don’t already know and I know this well enough myself. Still, sometimes one needs a reminder and hopefully finds some individual account of a lone voice screaming against the Amtrac treads of history grinding bones to meal. And it’s at that point that one can do nothing but marvel. I’ll give you a little example: Recently I was reading Jahrgang: 1902, which I think is called Class of 1902 in English. It’s not about a class that matriculates in 1902, though, but rather about a group of boys who are born in 1902. They’re obviously too young for the Great War, but are at just the right age (and right time in Germany) to valorize war and all things martial, and to fantasize about soldiering as feverishly as they dream of sex. Speaking of sex, there’s a scene early in the book in which the young protagonist, having heard pray tell of this act, arranges with a local rowdy to watch him perform the horizontal mambo with a young girl in the town who’s willing to do it for money. A plan is arranged for our protagonist, E. (his actual name in the book) to pay this boy a nominal fee (plus the fee demanded by the girl) to watch them roll around in a nearby field. It’s planned without the girl’s knowledge, and E. takes up a comfortable but hidden watch where he can play spy and sentry. The rowdy and the young girl lay in the field, proceed to copulate. As they go at it, the sex becomes more intense, and the girl first begins panting, then starts to moan. E. is an innocent who hasn’t been briefed on the details and mechanics of sex, and has only the scantest information which he was able to glean from schoolyard rumor and innuendo. Thus he’s confused about the mystery being revealed to him, although he’s obviously already started to undergo puberty, with an older female relation asking his parents at one point, Hatte die Junge Pollutionen bereits? (“Has the boy had pollutions already?”). He freaks out, shrieking at the horror of the secret world that sex conceals. It is simply nothing but murder! His screams naturally terrify the two who, regardless of their low caste, cannot afford to be caught in flagrante in public making love on the heather. E. turns from the scene, runs in terror toward his house. As he makes his way home, however, he senses a strange level of activity, a bustling among the townspeople whom he passes as he runs over footbridges and stumbles across the cobbles. He’s convinced that the word is already out about the pimply kid murdering the young prostitute for his personal edification. When he gets home, E. finds his father standing there. The setting of the house is described as Biedermeier-esque, staid and solidly middle class, with the parents being educated and steeped in the life of the mind in a way that would have been unheard-of but a couple generations ago in Prussia. The father looks at the son gravely, confronts him. The son braces for the conflict. Most of the people in the town are products of peacetime. The father is no exception, though there is some talk starting to brew that the lack of violence since the Franco-Prussian War is causing people to become enervated and for their lives to become meaningless. Not only does the father not strike E., though, but he tells him grimly why the town is an uproar. No, not because they heard about E. watching those two unsavory kids getting busy in the heather. Something far more momentous has happened: The Archduke Ferdinand has been shot in Sarajevo. E. inwardly heaves a great sigh of relief, realizes that he’s not in trouble, that no one knows about him paying the young couple to have sex. All that happened was some minor noble he never heard of got shot in some city he at most heard mentioned once or twice in class, if that. History is indeed very small sometimes, and the feelings and fears of the individual are very large. But we only know that because some people are still screaming to us across the chasm of time to please stop killing each other. Sure, maybe we can’t; maybe it’s too deeply engrained in our DNA, but try to spare a thought for the ants getting trampled beneath the feet of the elephant, from time to time. And more importantly, try not to get trampled yourself. But if you do get trampled, and you survive the stomping, make sure to write a book about the experience so that you can warn those who have not yet even been born what’s in store for them when they get old enough to kill and make love.

0 Comments

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed