|

Schrödinger’s Litterbox: The Internet, the Principle of Subatomic Superposition, and How to Kill Fewer Cats There are few scientific concepts as misunderstand or misrepresented as that of Schrödinger’s Cat. In fairness to those who fuck it up (myself included), it is a mindboggling concept. It only grows more mindboggling when one realizes it’s not just a concept or principle, but as real as gravity. I almost wrote “as observable” as gravity, but gravity is mostly observed by its effects, not by itself.

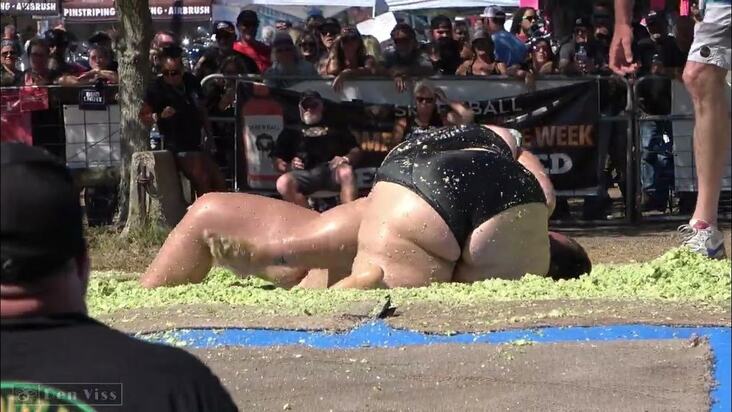

In the simplest terms, Schrödinger’s Cat is a way to visualize quantum “superposition” in a way that even the layperson can kinda sorta understand it. Superposition holds that the rules of matter are easy to understand provided we’re dealing with atomic matter. Get down to the subatomic and things get weird. A subatomic particle, in fact, exists in a state of superposition—both/and—until directly observed or measured. In other words, the subatomic particle is doing two things at once until the scientist actually takes a look at it. In real life, a cat trapped in a closed box where a boobytrapped phial of poison may or may not have been opened is either dead or alive. The idea that it’s both alive and dead until its state is observed or measured is supposedly just an atomic-sized metaphor for subatomic particle behavior. In the Coen Brothers film A Serious Man, about a physics professor having a crises of faith, he explains it to his student one-on-one thusly. “The cat is just a model for the math. The math is what’s real.” Not to mention important to the kid’s grade. “Even I don’t understand the cat,” the professor says. There’s a problem, though, with pretending the cat is just a model or metaphor, rather than existing in superposition itself. If you put enough subatomic particles together, you get particles. Put enough of those particles together and you get matter. Whether it’s organic or not is a matter of chemistry. When exactly subatomic particles behave as particles touches on the concept of flocculence. This is particles aggregating to become bigger things and is best understood by engineers with a strong gasp of good old-fashioned Newtonian physics, i.e. an apple that either falls from the tree or doesn’t. Trying to figure out when a bunch of “little things” become one big thing—or a bunch of little things is also one big thing—touches on the Sorites Paradox. That’s philosophy. But you see then that the cat being both alive and dead is in fact, not a just model. It’s just a question of when its reality becomes observable to us, and how. Turns out the professor in A Serious Man wasn’t being humble or facetious when he said he didn’t understand the cat. He was simply wrong in seeing it as a metaphor for the math (or rather, the Coens, like most people who touch the subject, were wrong.) The cat only becomes one thing in one state—alive or dead—after being observed or measured. And yes, hearing the cat meow or the scratch of its claws against the inside of the corrugated box counts as measurement. It’s at this point that even the biggest of big brains disagree on exactly how many cats there are, though. Or whether the cat you observe—dead or alive—is the only one left of the original two. Nobel laureate Niels Bohr believed in collapse of the wave function, a thing represented by this cool little pitchfork symbol, 𝚿, which is just the Greek letter “psi”. Once you opened the cat’s box and saw whether or not it was alive or dead, you turned the superposed cat into a single living or dead cat. At least according to Bohr. Congratulations, you’re a magician. Another scientist though, named Hugh Everett the Third, claimed that it only appeared you and your eyes had collapsed those two cats into a single one. Rather than collapsing the wave function, you were simply riding one of the propagated waves. It appeared to collapse because you are just one you at a time. The you who opened the box and sighed with relief to see the cat hadn’t tripped the poison mechanism is just one of you. Another you (with whom you’ll never interact) opened the box and saw, much to his horror, the little butterscotch tabby curled up, lifeless in the box. This other you turned out to be a shitty magician and should also seek therapy from the resulting guilt and trauma of poisoning a cat. Who, then, among the big brains is right and who is wrong? For a long time, most people thought Niels Bohr was right and Everett was wrong. Partly this was because they knew about Bohrs’ theory, as he was a well-established and well-funded, much celebrated Nobel Laureate who enjoyed institutional support. “Everyone,” as the currently en vogue Bin Laden once observed, “loves a strong horse.” Meanwhile Everett was just an ill-mannered, chain-smoking young man whose doctoral thesis faced many challenges. He was prickly even among a normally contentious and prickly group of (mostly) men not known for observing the social graces. As his academic career floundered and his papers moldered in some Harvard subbasement, he became even harder to deal with. He drank heavily and did R & D work for the military industrial complex, and the secretaries he sexually harassed claimed he had bad BO. He had a couple kids, too, one of whom committed suicide, and another of whom is the lead singer of the popular indie band, Eels. Scientists, despite the cosmic scope of their remit, can be petty, vain, as given to the picayune vagaries of human emotion as anyone else. Academia is a cutthroat Machiavellian world where resources like tenure and grants are scarce, and fought over more tenaciously than rare oases discovered in the desert. I only survived to get an MA, and every moment I spent on-campus I felt like I was suffocating, my ribcage contracting until my chest hurt. And if Everett were right, he was basically putting his cigarette out on Bohrs’ addlepated skull. Not only that, but scientists would have to contemplate the deep philosophical and moral implications of a multiverse, not because they wanted to, but because the math led there. With the passage of time, though, Everett’s theory has come to be not only accepted, but embraced by many, and not just hack SF writers like yours truly. To those who don’t have to bolster their supposition with mathematical proofs—i.e. artists, screenwriters, philosophers—Everett’s idea is the more interesting, the more savory. Its implications are definitely more metaphorically resonant, too. Just remember that the cat isn’t a metaphor, though. The cat is a model for a reality, whether you think that reality consists of branches or a single line. It’s only metaphoric to the extent the metaphor lets you visualize what you can’t understand when written out in equations that span multiple chalkboards. If you’re the kind of person who quails before math problems that involve Roman numerals, you definitely have no business getting near the ones that need Greek letters, too. Be thankful for the cat. For myself, the model-metaphor involves another box, and rather than a cat, a man. The box in this example would be the computer screen on which these words are being typed, and the man would be me. Sitting here, now, I can sense (but obviously not see) the various branches I could take myself on just by typing. I could write a well-written sentence or a shitty one. I could potentially close this MS-word window out now—without saving this document (no big loss) and search the dark web for guns and pills. The fact that I’m even thinking about it (or at least facetiously countenancing it) means on another branch there’s probably a me already doing it. This me is either soon to have an Uzi micro and a prescription bottle of Perc 10s in hand, or is soon to be cuffed by an ATF agent. Sometimes just thinking about doing something, I’ll feel a little breeze, or at least imagine I’m feeling one brushing past me. Is that me going off on another branch, I wonder, succumbing to the impulse there while the more circumspect me remains here, riding this spear? If I reconsider again, and cave to the urge—especially if it’s sinful or ill-advised—I’ll feel the wind again, probably because I’m hopping onto another spear. Call the personal computer hooked up to the net Schrödinger’s Litterbox, then, a kind of container that’s only as pure or dirty as the creature using it. Some use it to read scholarly articles on the latest development in crater-sited coronagraphs and its implications for direct imaging astronomy. Others use it to watch BBWs wrestle in kiddie pools filled with vanilla-flavored custard. Some—sui generis renaissance men—like me, do both.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed