|

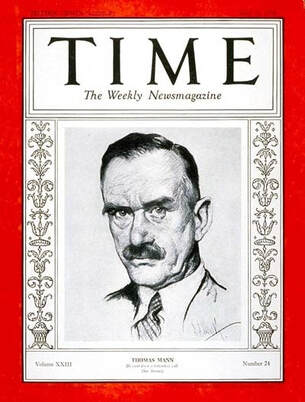

War is the cowardly evasion of the problems of peace.” I can’t find the quote online in the original German, but it’s attributed to the German writer Thomas Mann. Most probably it was excerpted from his Gedanken im Kriege (Thoughts in Wars would be a direct translation). It’s a quote that’s come back to me time and again through the years.

I suppose one’s first reading of the quote would be to view it as antiwar, but I’m not quite sure that gets at the heart of what Mann was saying. War sucks, sure, but inherent in Mann’s words is the idea that peace is even harder. Peace comes with its own burdens, which, believe it or not, make war a kind of psychic relief from the complexity and nuance that some people find excruciating. There’s some Bukowski story I read a million years ago that’s relevant here. Buk’s alter ego Chinaski is sitting in a bar (or maybe a bus terminal, I frankly don’t remember) and some hippy kids sidle up to him. One of the hippies, wearing a grimy army surplus jacket, asks Hank his opinion of war. To which Hank characteristically responds: “When you to the grocery store, that’s a war. When you get into a cab, that’s a war.” Melodramatic? Maybe, but I think he’s right that ultimately everything is a war. He even had a poetry collection titled War all the Time. I can’t remember exactly what the hell I was thinking when I joined the Army. It was only a little more than a decade ago but it might as well be ancient history, lost to the mists of time. All I know is that at the time I walked into that recruiter’s office, I was feeling pretty desperate. I was a classic failure to launch, a wannabe writer in his mid-twenties living at home with his mother, gradually growing weirder and more pathetic by the day. For a couple years there, I worked as a pizza deliveryman, but I didn’t enjoy having my car pelted with rocks by kids in the public housing complexes. The deductible could only cover so much, and only so many times. Also, the idea of potentially losing my life over a Meat Lover’s Supreme and a two-liter of Mountain Dew seemed ignominious, even for a creature as pathetic as I. Eventually I wisely quit that job. After that, I supported myself (to the extent I could) by taking whatever jobs I could land through a temp service. For a time there I had a decent gig doing background checks for a firm called General Information Services. I sat in my swivel chair, squinting under the fluorescence, sneaking looks at the legs of the women around me, crossed and sheathed in black or tan stockings. Alas, that gig didn’t last, and after an excruciating stint working at the Otis Spunkmeyer muffin factory, I decided I would rather risk dying than continue living this way. I’d threatened to join the army a couple of times, but my mom had always dismissed my threats as hollow. One day, though, I drove the recruiter’s office where it was located in the center of a suburban shopping plaza with a brick and stucco facade. They must not have been getting much traffic, as I literally had to rouse the buck sergeant behind his desk from a deep sleep. Later that night I went home and told my mother what I had done. She promptly called my father, which shows the gravity of the situation, as he hated her and she hated him. I don’t remember much about what they said (I was already locked in my mind, lost in my own zone at this point). I just recall her shouting, “Yeah, but I didn’t think he’d actually do it!” I was in terrible shape physically, but somehow forced my soft and flabby body through the whole nine weeks of basic training at Fort Benning. I did not emerge from the experience “Born again hard,” as Gunnery Sergeant Hartmann observed of Private Pyle in Full Metal Jacket. But on the plus side, neither did I put a round into my DI’s chest and then fire one through the back of my skull, either, a la Pyle. The military simplified everything. In the real world, I had felt constantly stressed about money. I had felt pathetic and poor and out of place, weak and neurotic and sexless, a loser in a society that only tolerated winners. Delivering pizzas, I felt like a bug with a slimy carapace scurrying up to the doorsteps of these stone McMansions filled with happy and prosperous people. I drove my mom’s crappy Aerostar minivan through the suburbs, surrounded by sleek, shining Benzes and big black SUVs (usually with impressive fiberglass speedboats tailed to trailer hitches). In the army, though, all of my bills were paid, meals were provided, and hierarchy was based on rank alone. And the loss of outward identity (down to shearing off my hair) let me develop a stronger interior life. I no longer felt insecure. I was too faceless, anonymous to pretend to paranoia. Who the hell would bother looking at me here? How could anything be personal where the drill sergeants barked at literally everyone, berating them with profanity-laced insults? Back in the real world, I had felt the constant ache of failure that went with not having a girlfriend. I’d definitely had no prospects for marriage, or the social or emotional skills to develop anything like a meaningful relationship. Every day after work, whether at Pizza Hut or Otis Spunkmeyer, I would smoke weed in my bedroom and masturbate to porn. I was wrapping myself deeper into a cocoon of seeming pleasure. But it was really just deadening everything inside me, including all ambition and the pain, which I should have recognized was unavoidable. It would have been healthier to face it and deal with the hurt and fear. But in the Army I was only around other young men, most of them horndogged up most of the time, just as sexually immature and crass as me. That said, a few already had spouses, real responsibilities, and even kids. Again, everything in the army was simpler, if not always easier. But I’m speaking only of the regimentation of Army life, not war itself. Eventually I got orders for my first duty station (Darmstadt, Germany) and from there deployed to Iraq (though we started out in Kuwait). The experience definitely changed me, made me more aware not just of my own mortality, but my humanity, as well as my heretofore undiscovered sense of shame. I was ashamed of what we were doing, and what I had done. The war had woken me up from the slightly unsettling dream that was my previous life, unpleasant but too undramatic to merit the title of nightmare. Is that easier, though, than living on the homefront in supposed peace? I think so. It probably requires greater fortitude to, say, clean toilets at a ballpark after a big game than to man a minigun while hanging out of a Blackhawk helicopter. Staring down at villages of mud huts, relicts of ziggurats, and fields of crops shimmering under a blazing sun at least offers scenic vistas of an ancient land. It definitely beats staring into toilet bowls, even when you factor in that toilet bowls, unlike the fields in Mesopotamia, aren’t seeded with men in burnooses with AK47s. Back when I was in the service, being a soldier still sort of conferred a certain kind of respect on the person serving. Being a soldier, I didn’t feel quite as alien or out of place in America anymore. I had passed through some membrane, performed some ritual required to psychically bond people across class and culture lines that was once an important aspect of becoming a citizen. Of course you sensed the cynicism beneath the praise and respect with which we were showered. The whole patriotism industry feted you because it was what big war profiteers like Lockheed and their lobbies and their rent boy politicians wanted. And guys who had the audacity to cite love of country as their reason for joining made sure to get the best sign-on bonuses they could, just like everyone else. But since you were the beneficiary of all this cynicism and you got all this smoke blown up your ass, you didn’t really question it. And naturally you knew that in their hearts of hearts, the Lee Greenwoods with their jingoistic yokel acts and the businesses giving soldiers discounts thought that we were suckers. And they were right. It takes a very special kind of mark to try to fabricate meaning out of dying for no reason, on behalf of people who deep down really don’t give a shit. Then think about the damage war does to the people in these impoverished countries, the goatherds and farmers growing their bitter crops in the mud. Think about the pain you put your family through, even if you don’t die or get severely injured, just making them worry about you while you’re downrange. But these are all thoughts I only have in hindsight, that, as most, were minor inklings, registering as mere cricks in the neck at the time. People would stop you in the airport and thank you for your service, too. Vets from previous wars would shake your hand, treat you with respect. Bearded, hippyish dudes who’d been in Vietnam might saddle up to you for a conversation, or an older man in suspenders might pigeonhole you to talk about war. Combat, of course, was a much more intimate affair in their days. And nothing we did in Iraq could compare with what happened at, say, Khe San, and definitely not at the Battle of the Bulge or Betio. But again, we were the recipients of love and praise, and whether or not it was misplaced (it was), it felt good and we didn’t question it. It isn’t just the praise and ego stroke that made being in the Army an alluring and ultimately simplifying illusion, preferable to living in the real world. Nor was it just the wearing of a uniform and feeling the high that comes with surrendering one’s will to that kind of fascistic power. It’s the way that being in the military breaks one’s life up into easily understood chapters. It gives one’s life a narrative aspect, a B.C. and an A.D. dividing line between the person one once was and the one they have become. These things happen in normal, nonmilitary life (I assume) in a more nuanced and complex way. Eventually you go from a boy to man, or a girl to a woman, without the delusions or pageantry. I remember coming home on one of my first leaves and feeling a great sense of pressure constricting around my chest like a band. And I remember another band fastening itself around my skull as if I were trying to take a nap in a house with a slow but persistent gas leak. I could feel that the people around me had been going about their lives—dating, working, struggling, in an unpraised but frankly admirable kind of silence. They bore the banality, the repetition, everything I had fled when I joined the army. They labored in a fog unrelieved by action, combat, awards, changes of locale imposed by whoever at Brigade level (or even higher) cut orders. To not be shuffled around the world, to wake up and face the same people every day—coworkers, spouse, children—seemed like a great burden. On leave I would go to coffeeshops or to libraries or to the pharmacy, and I would just steal glances at the people working there. I’d marvel at their bravery, their ability to endure this nondescript, unbroken continuity of time lived in the same place, basically the same day, relived again and again. Their identities and lives were organic, not something handed to them by someone else. Their time was not bisected and parceled, sliced and shuffled by some clerk at Operations deciding whether to send them to Fort Bliss or Fort Huachuca. Sure they had to work eight or even twelve hours a day, but when the day was done their time and mind was theirs. In the Army, even when we shammed and hid from work, our lives and bodies and souls belonged to the institution. We could mock it and make jokes, develop codes to express our disgust (FTA supposedly meant “Fun Times Always,” but everyone knew what it really meant). But we had exchanged something we could never get back, something that everyone else still had. A lot of the civilians I stared at on leave seemed happy. And many of those people no doubt were happy. But I think they were brave, too. A lot braver than me. I think, ultimately, that Thomas Mann was right about war being a cowardly escape from the problems of peace. Assuming, that is, he actually said it.

4 Comments

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed