|

Awhile back a writer buddy of mine mentioned he had a book in his to-read pile with the title of Nobody wants to read your Shit. He never got around to reading it, telling me, “I’ve had enough tough love,” or words to that effect.

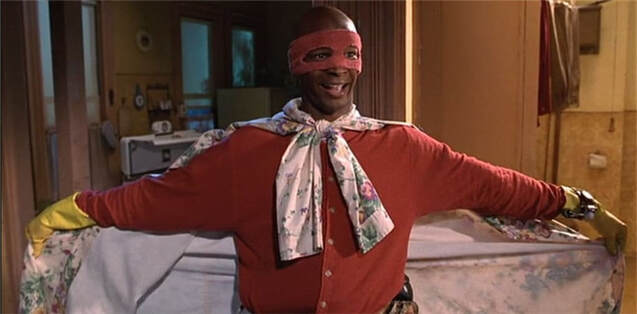

I personally never tire of finding new ways to remind myself that I suck, and so I decided to give the book a whirl. The book is as direct as the title suggests. The author is a successful writer who started out working on Madison Avenue and later had success writing The Legend of Bagger Vance, a story about a numinous negro who helps white protagonists work on their golf handicaps. One of the author’s insights is that the mechanics of storytelling may have some universal features across all times and cultures, but there are certain idiomatic quirks from country to country it still helps to be aware of. For instance: in American stories, the main character must be the ultimate agent of their destiny. People in other cultures (he cites the Russians) are more comfortable viewing the protagonist as the plaything of forces stronger than himself, whose self-realization (or progress over the character arc) comes when they realize they have no control over anything. But your American character, whether he or she fails or succeeds, should do so by his or her own hand, if you hope to have a readership larger than six embittered, beard-stroking baristas. One could speculate on the reasons that this is so, assuming one accepts the premise (and I guess I more or less do). America is a relatively young country that has never lost a war on its own soil. Or, in the delightful phrasing of poet Charles Bukowski, “The problem with these people is that their cities have never been bombed and no one has ever told their mothers to shut up.” It’s easier to believe in the ability of one person to challenge the world and win when it’s so deeply engrained in our collective cultural DNA. Whether it’s true or not is beside the point; we respond to films like Rocky, giving our cynicism a little caesura for a couple hours no matter how deeply rooted we think it is. The quintessential American is Horatio Alger, writing about young, impoverished boys pulling themselves up by their bootstraps to rise to positions of wealth and prominence. The quintessential Russian tale is Nikolai Gogol’s lowly clerk in The Overcoat, who scrapes and saves for a new garment and still ends up freezing to death. I think Dostoevsky or Tolstoy even said words to the effect that We all came out from beneath Gogol’s overcoat. Are there exceptions to this rule, though? Distinctly American tales in which the main character is someone to whom things happen rather than one who does things? Men and women, who, in grammatical terms, are indirect objects rather than subjects? I think so. For the sake of argument, take Goodfellas, starring Ray Liotta as Henry Hill, the mafia associate made famous for his betrayal of various Luchese Family bigwigs. I won’t recap the movie’s plot, nor its brilliance, nor its cultural permanence in cinema. It would be as absurd as me trying to describe the music of the Beatles to someone. Either you’re familiar with the work or you’ve been living feral and in the woods, too busy foraging for food and evading predators to bother with pop culture. Goodfellas’ relevance to my ramblings is that the central character of the film is a man seemingly without qualities. He is adrift in a sea of larger-than-life personalities, men willing to use violence over the slightest perceived insult, men who are basically supernovas of unbridled passion exploding in every direction. They have massive appetites for sex, money, and literally food in the cases of some of the more rotund and fleshy gindaloons. And because they have the muscle to break anyone who might thwart them and the resources to keep the party going, there are basically no checks on their behavior. Watching the waspish establishment types trying to corral hotblooded Irishmen and Italians like Tommy and Jimmy as they go on their crime sprees is like watching an overworked superego trying to reason with an irrepressible id. But Henry is mostly a cipher, a dud. Despite being the main character, and being a naturally motormouthed raconteur (most of the film consists of his voiceover narration), he does very little. Even the violence done by the mob on a daily basis is something he mostly watches, usually with a mixture of dread and horror in his eyes. He’s most a spectator in the film’s key scene, in which his crew murder made man Billy Batts. It’s this act that divides the mafia (and America) into two separate eras, one where rules and tradition are mostly adhered to, and another in which they are jettisoned and disillusionment sets in. His involvement in the infamous killing consists mostly of cleaning the “skunk” smell of the man’s corpse from the back of his car’s trunk. Later, when the body needs to be dug up and moved to another location, he spends most of his time puking his lungs out while Tommy and Jimmy do the digging. His one major act in the film is to rat on his friends. And because this act essentially strips him of whatever identity he had, it only compounds his cipherhood rather than giving him agency. Henry ratting immediately unpersons him in the eyes of his friends and even to some extent in his own eyes. He notes as much in the film’s final scene after getting resettled by Witness Protection, as the camera pans over drab suburban tract houses plotted to the featureless flat horizon. I get to live the rest of my life as a schnook, a nobody. The blandishments that came to Henry as criminal- the closetful of Italian suits, the wingtip shoes, the sugar bowl full of cocaine- were the only things that gave him any sense of self. And now they’re gone. Interviews I’ve seen about the real Henry Hill only confirm the impression of a man who wasn’t there. His own sister in one interview expressed her lack of shock that her brother would rat people out. “Henry was always a rat.” And yet it’s because he’s not much of a “doer” that Henry Hill makes such a good observer. Even in the grips of a cocaine-induced nervous breakdown, he remains a reliable narrator. That, I suppose, begs the question: is the man/woman of action not the best person to relate events? Is doing in and of itself something that precludes one from seeing, or at least relating? I’d be tempted to say “Yes,” or at least entertain the idea, if there weren’t so many ready examples to the contrary staring us plainly in the face. Take the droog Alex in A Clockwork Orange. Like Scorsese’s Henry Hill, Kubrick’s Little Alex loves to talk. His voiceover is delivered in the Nadsat argot invented by author Anthony Burgess, rather than the Queens’-Brooklynese of Henry Hill (who related his exploits to crime scribe Anthony Pileggi). But Alex, unlike Henry, is the agent of his own demise and (ostensible) redemption, despite being the plaything of institutional sadists first in prison and then in the medical profession. He finds the time to do everything from raping women to bludgeoning his friends for disobedience, all while keeping his running commentary going. All this is beside the point, though, as Alex is British, not American. That said, it’s worth considering that the person who doesn’t do but merely sees does have roots as an American archetype. Take Nick Carraway in The Great Gatsby. He mostly lives at a remove from the wealthy and beautiful people around whom he orbits, attracted and repulsed by them so that he inhabits a kind of moral Lagrange point ideal for seeing without acting. Nick cannot join the club because he is not rich, anymore than Henry Hill can join the Mafia due to his Irish ancestry on his father’s side. Maybe that’s the key insight to take away from these only tenuously connected musings. Some central characters are observers rather than actors because they frankly have no choice. It isn’t that this type is not as American as apple pie; it’s that the recoiling at this state of affairs is the outgrowth of a specifically American disposition. The Russian would likely just accept it as the natural state of things whereas the American sensibility lashes out against it. Deductive logic would tell us that as America collapses on itself, our films should become more mature and self-reflective, or at least nihilistic. That hasn’t happened, though, as the Dream Factory seems to churn out more and more movies about superheroes saving the world. This attitude certainly made sense in the postwar years of heady optimism, where America was flush with pride after defeating the Axis powers in the Second World War and standards of living were rising across the board. What it portends now, aside from a deep sense of denial, is anyone’s guess. Perhaps I should just leave you with the bardic sagacity of comedian Dave Attell: “When you’re a kid, you think your father is Superman. As you get older, you finally realize that he’s just an alcoholic who walks around the house in a cape.”

0 Comments

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed