|

SWERVING ON THE SUPERNATURAL: SOME RUMINATIONS ON GENRE

Earlier today I finished writing a short story, tentatively titled “Last Turn of the Old Wheel.” Actually, I like the title enough that I can probably stop referring to it as “tentative.” I think I’m going to stick with it, when I submit it into the world for publication. Since talking about one’s work is only slightly less tedious than relating the details of one’s dreams, I’ll try to be brief in my summary of the story’s contents. It’s about an old man, who once was a cabdriver and is now housebound and cared for by his grandson. The old man is slipping into senility, but still retains enough of his faculties to mourn for all the things he’s lost, especially his erstwhile identity as a cabbie. To compensate for the old man’s sadness, the grandson gives him one of those racing game simulations, complete with a steering wheel, clutch, and pedal setup. His grandpa is happy, until the Gamestop where the grandson rented the equipment wants its console back. The place is closing down, and since the grandson is living on the poverty line, he can’t afford to buy a system. And since there is no other game rental store in the neighborhood, it looks like grandpa is going to have to go back to staring at the apartment walls. Until, that is, a techie who homebuilt his own proof-of-concept console offers his gaming system to the grandson, for a song. The kid naturally scoops it up and brings it back to his grandpa, presenting the currently morose man with the gift. Like most old people, the grandpa is reticent to try new things, especially since he’s still smarting from being forced to forfeit the old game system. Slowly, though, he begins to acclimate to the new one. It's not hard to do, as the new system is not only an incredibly real simulation, but centers around driving a cab around the city rather than something fantastic like street racing. All is going well, until grandpa gets into a “car accident.” The quotes are necessary, as the accident is confined to the virtual realm, and shouldn’t be a big deal. Except at the exact moment where the grandpa’s virtual avatar wipes out onscreen, a real wreck occurs outside the apartment window. Unfortunate coincidence, or something more? If you’ve seen enough “Alfred Hitchcock Presents,” “The Twilight Zone,” or read or seen any number of horror anthologies, you can guess how this might go. There are three basic options here:

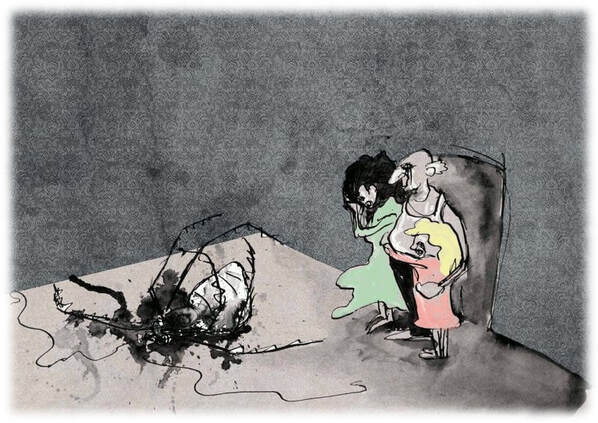

This is an old problem, one which has existed in popular SF and horror for decades, as evidenced by my previous allusions to Hitchcock and Serling. Despite all they both contributed to popular culture, many of their showcase stories end up being too clever by half, especially in the last act. Especially with their overreliance on irony and the O. Henry twist ending. In Hitch’s case, this moment is usually accompanied by a few upward trilling notes on the flute. The main character might even break the fourth wall and look at the viewer when the dog digs up the wife’s body, or the plotter’s otherwise perfectly orchestrated villainy is undone by some minor bagatelle. The technique of the twist ending can be used not just to powerful, but profound effect—see both the “Alfred Hitchcock Presents” and “Twilight Zone” iterations of Ambrose Bierce’s peerless story, An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge. Most of the time, though, the viewer or reader can almost smell the flop sweat sliding from the brow of the storyteller as they struggle to write their way free of the corner into which they’ve unwittingly maneuvered themselves after two acts of tap-dancing. A great example of this is the film, I Bury the Living, about a cemetery caretaker who discovers he merely needs pushpins on a corkboard to kill a man. I won’t spoil the film’s big reveal here, for those who haven’t seen it. Suffice it to say, though, that horror maestro Stephen King is right when he says the film’s author would have been better off leaving the spooky source of the caretaker’s magic a riddle. Nothing about the mundane meddling that only appears supernatural in the runup to the reveal makes sense, when considered for any length of time. The film would have been better off going with option one or two. If one uses the unreliable narrator technique, the issue may never really be clarified. The source of the conflict might be mundane, but the narrator is crazy or superstitious enough to think it supernatural, or vice versa. Stephen King’s critique of Stanley Kubrick’s adaptation of his book The Shining very much hinges on a quibble of Kubrick’s swerving the supernatural. The book is very much about the supernatural explicable (King is a moralist), but Kubrick, an existential materialist, makes the story about the unreliable mental state of Jack Torrance. Since the guy playing Jack Torrance is Jack Nicholson, and Nicholson always looks batshit crazy, this works, at least for Kubrick and those of a similar Weltanschauung. There is of course another, final and fifth category of explanation (or lack of explanation), which I’ve heretofore overlooked. That would be the absurdity of the unanswerable, the inexplicable even by recourse to magic or handwavium. This is the kind of unresolvable resolution preferred by Kafka, by Dadaists, surrealists, and existentialists. These artists many times view consciousness itself as a trick, a cursed quirk of evolution that causes us to seek and expect solutions and sense from a universe under no obligation to supply them. The universe indeed might lack the consciousness we have, an endowment we either received from ourselves through solipsistic striving or some other freakish accident of egotism. This is where the lack of an answer at the tale’s end seems to suggest less the supernatural than the complete absence of anything extramundane or even something that can be apprehended with the laws of science. How or why anything happens can’t be explained away as being due to a spell, or hinted at as some kind of sorcery invoked in contravention to the usually obtaining laws, or even via some invention that widens human understanding and possibility to see the underlying laws at work. Recourse to neither Bible nor electron microscope, nor parapsychologist’s electromagnetic wand will reveal what is ultimately afoot. Some force is thwarting or Metamorphosing the character or their world—keeping them from reaching the Castle, putting them on Trial for unspecified crimes—to make a larger point about the remoteness or absence of any higher power, or meaning. There is no hope or explanation, only absurdity, and the only option is to laugh in the dark, alongside the dark, or have the darkness laugh at you while you weep and claw blindly at unyielding walls. Either find the funny in your plight or find yourself the butt of a joke whose teller might not even exist. Obviously this kind of existential, illogical surreality isn’t seen often in popular fiction, especially not on “Alfred Hitchcock Presents” or “The Twilight Zone.” I suspect such unsatisfying, resolution-free stories—free of climax and catharsis, full of frustration, lacking narrative symmetry—wouldn’t have sat well with advertisers. It makes a kind of sense, after all. For who the hell is going to be in the mood to buy soap or toothpaste or beer after having it relentlessly hammered home that there is no god and no hope? Or, as Kafka said, smiling, “There is hope, but not for us.”

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed