The Blind Ride the Light Beam; Or, Needing Words to See?Lately I’ve been reading an old, but-still-relevant book on cognitive science, Steven Pinker’s The Language Instinct. To give a brutally brief summation here, his argument is that language (the thing I’m using to write) does not give the mind its structure. The mind has its own language and rules for that language—syntax—and all the languages we see in the world are products of this thing in the brain. The linguist Noam Chomsky called this thing the Language Acquisition Device (LAD). Contained within the LAD is the Language of Thought (LOT), a term coined by cognitive scientist and philosopher Jeremy Fodor. Think of the LAD as the hardware and the LOT as the software program, and you’re in the neighborhood.

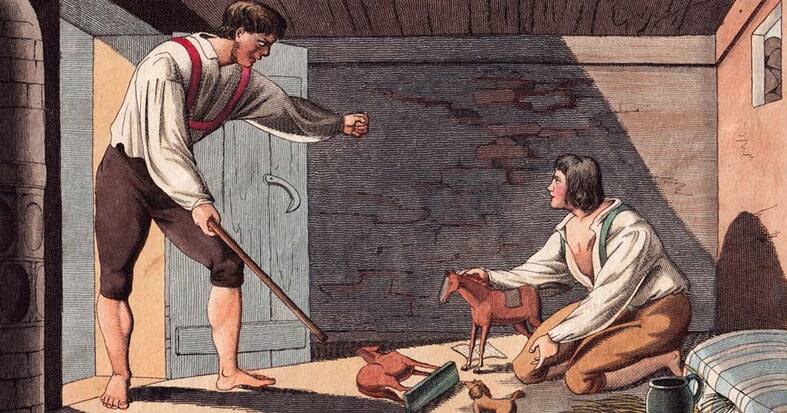

Pinker doesn’t really have a beef with either Chomsky or Fodor. He simply thinks that evolutionary theory can explain more of the workings of this hardware and software than Chomsky seems to think. There’s a smidgen of lese-majesté directed at Chomsky in the book, but that’s mostly Pinker taking umbrage at how inaccessible Chomsky’s work on grammar is to the layman. Pinker, like, Malcolm Gladwell or Ben Bova, shrinks down big concepts so that you can get a reasonable grasp on them during a single plane ride. You also won’t annoy fellow passengers by spreading out a bunch of notebooks and bulky texts on your tray table trying to grasp the concepts. In the book, Pinker is careful to qualify his assertions, and to admit that the mind is not only an incredibly complex organ but a dynamic one. New pathways can be lain down and old connections can grow weaker. Functions supposedly handled by one hemisphere of the brain can involve other regions inexplicably—contra not only received wisdom, but hard neuroscientific data. Such inexplicable “teamwork” and sharing of function has been observed in everything from PET scans to MRIs to experiments involving those head electrode stickeys attached to skullcaps that look like colanders. The brain has over one-hundred million neurons and over one-hundred trillion potential synaptic connections, which is greater than the number of stars in the Milky Way. This means that we don’t just have a long way to go in understanding the human brain. It means, rather, that we will probably never understand it completely, because it continues to change. It lacks unlimited space to expand and is not flatly Euclidean like our universe (probably), but it still an infinity unto itself. Everything from air pollution to digital pollution has an effect on it as well; there is some evidence, in fact, that constant cellphone and internet use has thinned the myelin sheaths of our brains, especially those of young people. Pick up a book written by someone in the 19th century and one by someone in the 21st century. More than likely you will observe massive differences in the lengths of sentences and sizes of paragraphs. It is a long fall from Marcel Proust to Chuck Palahniuk (no offense to the author of Fight Club.) That the brain and the world interact makes it hard to say which exerts the greater effect on the other, at least where language is concerned. The baby’s brain begins to form around the third week of fetal gestation—which gives the brain a head start. But it’s only a matter of months until that baby is delivered and is immediately bombarded with words from its mother, the doctor, and nurses. Another issue with trying to unriddle this chicken-egg relationship between the brain’s language and literal language is the variability in how human brains work. Think of any time your doctor or someone else gives you some new information they want you to assimilate. Remember that form they give you, which asks for your preferred learning style. Would you learn better with visual aids or with a written description? For those of us who are word-obsessed, the picture is best seen in the words. Yes, as paradoxical as it sounds, I see pictures in words better than I see them in pictures. I don’t think I’m the only one with such a predilection. It’s a fine line between Bibliophilia and bibliomania. In an early poem Charles Bukowski cautioned, “Beware those always reading books,” and maybe he had a point. Maybe there is something wrong with people like me who need words to see. I imagine there are also people with the inverse problem, too. I’d hazard there’s more than one autodidactic auto mechanic (say that phrase three times fast) who’s illiterate but can fix your car, no trouble. Let him look under your hood and you’re going to get much further than you would with me reading a troubleshooting manual to you. Even if that manual is comprehensive and written by a master. The map is not the territory and a 2D diagram is not a three-dimensional engine. The director Tim Burton says that when he was first offered the Batman film, he balked, claiming that he hated comics as a kid. He didn’t know the order in which to read the narrative boxes and thought bubbles. I, being the weirdo I was (and am) would usually only read the words, getting the images from them. I’d be halfway through turning the page when a little voice in the back of my head would scream Go back and look at the pictures! Someone spent a lot of time on drawing them, inking, and coloring them. We’re all maybe slightly synesthetic, tasting colors or seeing music. The part that is strongest with us—the cognitive in me, the visual and conceptual in Burton—probably compensates for weaknesses elsewhere. How exactly this affects the software in our brain—the LOT—is beyond me. I think it’s fairly safe to say that this overdeveloped “word” or “picture” muscle has no effect on the hardware—LAD, the box in which the mind’s internal language sits. That cake is baked before we hear anyone speaking, as the baby doesn’t even have fully-formed, functioning ears until the sixteenth week, at the earliest. The brain is ready for language and pictures well before the eyes are ready to read comic book panels or stare at Batman throwing a Baterang. For those like me, though, I think words and language are necessary not just for thought, but for true sight. And because we begin speaking very early—especially if you count a baby’s echolalic babbling—we see from pretty much the beginning. Even if we only see with words. Lack the words and perhaps you will lack the sight. Many of the stories that support this idea are apocryphal, but that doesn’t mean they don’t contain some truth. Recall what that man aboard Captain James Cook’s ship said in his diary about the natives ignoring the approach of the English fleet. The myth has also been imputed to the Conquistadores who arrived on the shores of the Americas. The cuirassed men carrying their blunderbusses expected to present a shocking sight to the locals. But the people of the Americas supposedly ignored them until their ships pulled ashore. It was only after the Spaniards descended the gangplanks that the natives grew animated and curious, and the bolder of their number approached the invaders for a better look. It wasn’t the lack of a word for ship that kept the natives from supposedly seeing the ship. It was the lack of a concept. A word doesn’t stop a people from grasping a concept, and when a language needs two or more words to describe something described in one word in the source language (SL), it’s an easily enough solved problem. The target language (TL) uses something called “kenning.” When the Vikings called the ocean “whale road,” they were kenning. When the natives made their first mistake of imbibing alcohol and dubbed it “firewater,” that was also kenning. And a tragedy. Remember also the story of the German foundling Kaspar Hauser, who appeared in Nuremberg in 1828, having supposedly been kept in cruel isolation by a sadistic warder up until then. He knew only a few phrases, like Weiß nicht (“Don’t Know”), though he could sign his name beautifully. Because there was such great cultural ferment at that time regarding human nature—the Enlightenment got to Germany later than France—Hauser became a cause célèbre. By studying Hauser and other foundlings and feral children, it was thought key issues about culture versus inborn nature could be solved. No one in Enlightenment Europe would have been allowed to conduct the kinds of “language deprivation” experiments previous kings had tried, but opportunities like Hauser’s would provide the Stoff for similar experiments. Did humans contain deeply embedded platonic ideals--ding an sich in German—a priori of seeing such things? And would one’s senses—critiqued so critically by both Goethe and then Kant—be even further atrophied by such isolation? Hauser’s custodians kept careful notes of his progress and setbacks—the Germans call these fastidious records Protokolle—which give us some clues about inborn versus socialized nature. What they learned about language was especially important, assuming, that is, you accept Der Protokoll at face value. There are those, for instance, who maintain the entirety of Hauser’s story was a hoax, and others who claim it was something much graver, part of a royal conspiracy to disinherit a potential usurper to the throne. Let’s put all that aside, though, and give what’s recorded and relevant a closer, hermeneutic reading: Early in Hauser’s stay among the Nürnberger, he was given a room with a beautiful view, as an act of kindness. But much to the dismay of his benefactors, when he looked outside, at the leafy lindens and flowing creek, he howled as if in pain. And because he had not yet learned to talk, he couldn’t even explain what had disturbed him so. Why had he reacted with such horror to such simple and natural beauty? Even Friedrich Hölderlin, the Romantic poet—plagued with schizophrenia and confined to a garret—enjoyed looking out his window when not composing. Had it been a simple matter of sensory overload for Hauser, after the many years of deprivation? Someone got the chance to ask him about this harrowing incident after he learned to speak, and it appeared in eine der Protokolle. Sadly, I can’t find the book in which I first read it, but will try to recreate a paraphrased approximation. Why did you shout so at the beauty? they asked. To which Hauser responded, I did not have the words yet, so I could not see the trees or the water or the birds. It was all a whir of vertiginous color. This being unable to “see the trees” sounds quite a bit like our old proverbial saw about “not seeing the forest for the trees.” This idiom even has its own neurological corollary. It’s rare as hell and an ungainly word to boot, but here it is: Simultanagnosia. It’s literally defined as the inability to see more than one object at a time. Incidentally, the German idiom for “forest for the trees,” is “den Wald vor lauter Bäumen nicht sehen...” Adding the modal infinitive “zu können” (just to give us a healthier fragment) would make the Redewendung (turn of phrase): “den Wald vor lauter Bäumen nicht sehen zu können.” In English, this would translate as “to be unable to see the forest before the loud trees.” The dative preposition vor could also be translated as “from.” Likewise could “laut” be translated in a more figurative sense (like we would describe a shirt patterned with palm trees and flamingos as “loud”.) I personally prefer to see those trees as literally screaming, though. Wasn’t there an old rock band called The Screaming Trees? If all this sounds like incredibly weak sauce to you, barely science (even social science) consider that we have proof of our own blindness to reality before us. We needn’t feel the anthropologist’s cultural relativist guilt over patronizing the aboriginals before James Cook or the Mesoamericans before Cortez. Neither should we feel too much pity for Kasper Hauser’s predicament of the lysergic color wheel that was the world before he had words to separate its elements, and thus see. How many people were even aware of the realm we literally inhabit, spacetime, before Einstein had his epiphanous vision of running alongside a beam of light? It’s literally all around us and is announcing itself each time we take a step, Zeno-like, in any direction. There’s probably less shame in not seeing a ship (or ignoring it) or shrieking insensately before a bucolic view of the landscape outside your window, a la Kasper Hauser. This massive perspectival shift—from three to four dimensions—is at least as great a leap as that from two dimensions to three. Assuming String Theory isn’t dead, we’ve all got at least another six dimensions to go—conquistadores, foundlings, physicists, and aboriginals all. That’s a lot more forest, a hell of a lot more trees. Incidentally, these massive shifts in thinking that occur in brilliant individuals then spread out to the wider culture, are described as Wendungen in German. Eine Wendung is literally a turn. Wendungen as used in philosophy refers not just to turns-of-mind, but explosions in consciousness. The jump from the tortured and flat two-dimensional paintings to those that gave a vivid sense of true perspective represent a giant Wendung / turning in arts. The leap from the unicameral, animist-integrated consciousness of primitive man to the bicameralism proposed by Julian Jaynes is also such a Wendung. If you’re thinking that you saw that word, Wendung, previously in this blog entry when we were talking about language, you’re right. The German word for turn-of-phrase or idiom is “Redewendung,” literally “speech turning.” Isn’t that something? And if you’re wondering, by the way, if playing with words—Redewendungen—can accidentally lead to one of those bigger Wendungen in consciousness, wonder no more. Read The Discovery of Mind in Greek Philosophy and Literature by Bruno Snell. The poets of Attic antiquity were struggling to find ways to describe the greatness of the gods and accidentally deified themselves, discovering that writing itself was an act of creation, a panegyric to human consciousness as much as to the gods on Mount Olympus. This led many to view the gods as figurative rather than real. It’s a short leap from there to Nietzsche, and potentially the nihilistic end of the human project. Whoops.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed